Social media feeds lately have been awash with commentary on race relations, statues, and the politics of historical memorialization. Tweets like this one, remind us to consider the ‘values’ of the enslaved at the time of the American Civil War when refuting the claims of those who support the preservation of statues on the grounds that individuals should be judged by the standards of their times. Other tweets have cited the Haitian Revolution as evidence that slavery was never considered widely acceptable.

This logic made me reflect on the overwhelmingly critical assessments of the founders of Liberia (and the long-lived ruling class they spawned) by academic and popular analysts alike. Will this new shift in racial discourse lead to more sympathetic or nuanced considerations of Liberia’s early leadership and the long-ruling True Whig Party?

The ‘Congo-Native’ divide is not only a charged issue within Liberia; it is one that shapes Western discussions of the country as well. The blurb of ‘Another America,’ a 2013 book by James Ciment, a white American author, offers this critique:

“…The Americo-Liberians struggled to live up to their high ideals. They wrote a stirring Declaration of Independence but re-created the social order of antebellum Dixie, with themselves as the master caste. Building plantations, holding elegant soirees, and exploiting and even helping enslave the native Liberians, the persecuted became the persecutors….”

Similarly, J. Gus Liebenow, one of the most significant early ‘Liberianist’ scholars in the United States, wrote in the 1980s that the settler element in Liberia embraced standards identical to “those of the antebellum American South. Far from rejecting the institutions, values, dress, and speech of a society that had rejected them, the free persons of color painstakingly attempted to reproduce that culture on an alien shore.”

Such views reflect the tone of much of the analysis and commentary on Liberia from the U.S. and Europe. In this new environment, will the defense of Liberia’s early ruling class (and its successors) by Tom Shick (one of the few black American historians of Liberia in the 1970s) receive more serious consideration? Will scholars start to more critically examine issues like the hypocrisy of the 1930s League of Nations investigation of Liberia’s role in the Fernando Po labor scandal in an era of widespread colonial abuse in Asia and Africa?

At a time when there is increasing (academic) interest in the role of black people in shaping transatlantic history, it is notable that Liberia is not assuming a more prominent role in these discussions. Furthermore, the most vibrant field of Liberian history focuses on the activities of colonization societies, white Western institutions, often relegating the efforts of Liberians to secondary considerations.

One of the few figures in Liberian historiography to achieve significant acclaim is Edward Blyden, the only early settler lauded in the wider canon of pan-Africanism. Notably, Blyden turned his back on Liberia in his later years and was primarily based in Sierra Leone.

Blyden’s contributions were celebrated by pan-African scholar Hollis Lynch in the 1960s and this early commendation facilitated a lingering interest in the life of the diplomat and President of Liberia College. A new biography of Blyden was published just last year. The recurring interest in Blyden prevents the emergence of a more multi-faceted account of the nation’s early years.

Contrast with Haiti

The relatively stagnant state of Liberian studies stands in stark contrast to that of the oldest black republic, Haiti. At the various academic conferences I’ve attended since entering a Ph.D. program in African history in 2016, I’ve not encountered discussions of Liberian efforts to ward of French and British land grabs during the ‘Scramble for Africa,’ an issue which one might expect would resonate with scholars in the current climate. In fact, I rarely hear about Liberia at all beyond the civil war and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. Conversely, I frequently come across think pieces in major outlets highlighting early Haitian leaders, or the nation’s case for reparations from France.

At the conference of the African American Intellectual History Society earlier this year, Haiti seems to have been a relatively common topic of discussion, whereas Liberia appears to have been roundly ignored. A quick glance at the conference program indicates that Haiti was the subject of a dedicated panel, roundtable, and the focus of at least two other papers, whereas there does not appear to have been any paper examining Liberian history, despite Liberia’s stronger historical ties to the U.S.

Differences between Haiti and Liberia extend to the legacies of their prominent early leaders. Toussaint L’Ouverture, the foremost liberator of Haiti, remains the subject of vibrant (and sympathetic) historical inquiry despite his background as a slave owner. Meanwhile, there is little current interest in Liberia’s ‘founding father,’ Joseph Jenkins Roberts. One wonders if, in the current charged climate, Haiti’s violent resistance to slavery will shift Western scholarly interest further from Liberia and toward the Caribbean island seen to embody more revolutionary origins.

Conclusion

The most significant efforts to carry forward the discussion of Liberia’s revolutionary status appear to be coming from Liberians themselves.

I’m eager to get my hands on Carl Patrick Burrowes’ biography of Hilary Teague, one of the great thinkers of the early Liberian republic. It’s also worth noting that in my several years as a Ph.D. student in the U.K., one of the few (perhaps only?) doctoral students I encountered researching Liberian history was Jacien Carr, a Liberian-American scholar. Back in the U.S., while the Liberian Studies Association (a U.S.-based organization with significant Liberian engagement) does not maintain a presence at major Africanist conferences (like the U.S. African Studies Association), it publishes a compelling journal and hosts its own fantastic annual conference – which was to be held at an Ivy League institution this year before a Coronavirus induced cancellation.

It will be interesting to track how the current moment shapes Liberia’s historiography. How current global debates evolve may very well determine if future scholarship on Liberia spurs efforts to challenge established assumptions, or further entrenches them.

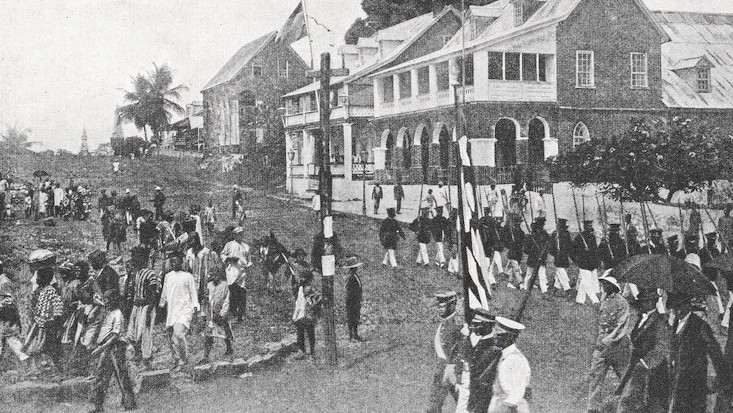

Featured photo by J. A. Hammerton