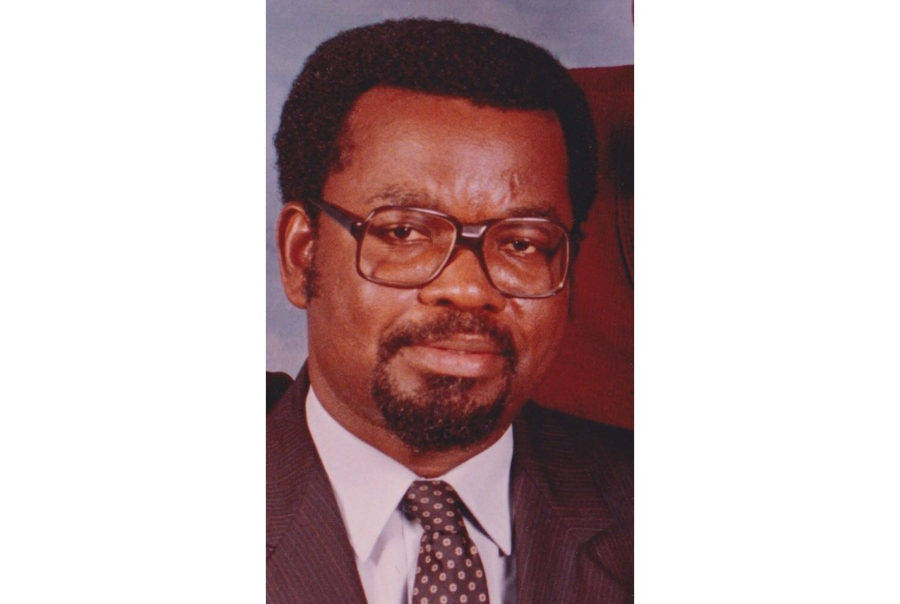

Byron Tarr’s older brother Phillip Tarr and I graduated Bassa High School together in 1960. Somehow, our paths diverged and the younger Byron entered my orbit in the late 60s.

As Byron and I received our terminal degrees in the United States in 1972, we began long and intense conversations about Liberia’s past, its present, and future prospects.

A bond was established then and it remained firm through the vicissitudes of Liberian national life since then, broken only with his passing earlier this month. Funeral Services were held at his home village of Zondo in Grand Bassa, where his remains were interred on Saturday, October 21, 2017.

As I pause to remember my friend, I extend heartfelt condolences to his family particularly his three surviving children – Stanley Byron Tarr, Seymour Bruce Tarr and Aimee Zeoweh Tarr.  Your dad loved Liberia with an uncommon passion and strove all his life to make it a better country. The records of his deeds are there for public examination and evaluation.

I walked into Byron’s office at the Finance Ministry in 1972 shortly after he took the job of special assistant/assistant minister of finance for revenues. I was on a visit home as a freshly minted Ph.D. We talked about the challenges facing the new administration of President William R. Tolbert, Jr. I returned to my teaching job in the U.S. but we stayed in close touch.

Finance Minister Steve Tolbert directly recruited Byron and though he held titles as an assistant, then deputy minister of finance for revenues, he became a highly regarded principal adviser to the finance minister.

When the history of Steve Tolbert’s effective though controversial stewardship of the Finance Ministry of the era is written, Bryon will perforce figure prominently. Remodeling the Maritime program, establishing systems for tax collection, chairing the committee that drafted Liberia’s first ever law toward strengthening the Auditor General’s Office, strides in government debt servicing, and creating an enabling environment for a vibrant Liberian entrepreneurial class were only some of the highlights of what transpired in the first half of the 1970s.

Two years later, I returned home with my family and joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. As the year 1974 came to a close tragedy struck my friend as he lost one of his twin sons to a drowning accident. Though this tragedy was the proximate cause for his withdrawal from government service and returning to the U.S. landing a job as a tax expert with the U.N. system in New York, there were also echoes of personal disillusionment with the administration.

However, by 1977, Byron was back in Liberia at the personal invitation of President William Tolbert. The new job was comptroller general of state-owned enterprises with a mandate to improve the sector, including privatizing some of the state enterprises.

But Byron’s responsibilities extended beyond public corporations, as he soon became an informal advisor to President Tolbert on matters affecting the national economy. As he brought to bear his intellect and passion for Liberia, I heard the president on several occasions marveling at Byron’s skills but also remarking: “You must have strong stomach†to digest Byron’s doses of advice.

A couple of years after Byron left the Tolbert administration for the second and last time, the military coup d’état of 1980 occurred. Byron was recruited with others to help stabilize a major national crisis. He remained engaged in the 1980s, serving briefly as minister of planning and economic affairs, a member of the National Constitution Commission that drafted what became the 1986 Constitution of Liberia, and among the founders of the Liberia Action Party along with Harry Greaves, Sr., Jackson F. Doe, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, and Nah Doe Patrick Bropleh.

He would soon pay a costly price for his political activities, for while he was serving as secretary general of LAP, he was arrested in 1985 by the military government of Samuel K. Doe, imprisoned and his house deliberately burned to the ground by Doe’s soldiers. Upon his release from prison, he briefly settled in the United States, but professional opportunities in short order took him further afield.

Travelling throughout the African continent and residing in several African countries for periods of time, Byron’s many professional engagement included contractual assignments with the United Nations Development Program, the United States Agency for International Development, the Africa Capacity Building Foundation, the African Development Bank, the African Union, the European Union and the World Bank.

Such professional opportunities abroad did not preclude his commitment to Liberia, for as the country descended into civil war, he was in the thicket of the goings-on to contain war and restore peace to his beloved country. But it was not peace at any price that he sought. He wanted a different, reformed Liberia of greater equity and justice.

Again, when the records of this dark period in Liberian history are fully uncovered, Byron Tarr’s uncompromising stances tending toward equity and justice will become evident. And so he became a part of at least the first interim governing arrangement during the war years, even serving briefly as Finance Minister in the Interim Government of National Unity.

Once a semblance of peace was restored to the country, Tarr resumed his private consultancy work. He accepted membership on the Core Team and leader of the economy team preparing the Liberia Vision 2030 long-term perspective study. His last major engagement was as the founding executive director of the Liberian independent think tank, Center for Policy Studies, which survives him.

Even as his health failed, he was being recruited by the Liberian Senate to serve on a panel of economic experts known as the “Independent Economic Review and Advisory Panel†to study and advise on the parlous state of the national economy.

I was visiting his home when he informed the President Pro Tempore of the Senate of his health inability and thus his decline of the offer.

In the last few years of his life, Byron was researching a book seeking to analyze the interrelationship of the political and economic architecture of Liberia by reviewing some three-dozen public sector reform projects Liberia and its development partners implemented between 1908 and 2008. Tentatively titled “To Rouse Liberia, Long Forlorn: Overcoming Challenges to Economic Governance,†the study sought to replace the politics of reform with the reform of politics.

Byron and I collaborated on a wide range of issues related to our country, among them the Vision 2030 exercise and the Center for Policy Studies. We provided critical editing to each other’s work. We even co-authored a book, Liberia: A National Polity in Transition (published in 1988). We worked well together for some 45 years in service to our ideals and to our country.

Good, ye my friend! You have played well your role! Rest in peace until we meet again!