The Peace Corps has announced that it is returning to Liberia after having pulled out volunteers during the Ebola outbreak. In this piece, a former Peace Corps volunteer, Nimu Sidhu, recounts how the Peace Corps held the first national science fair after the civil war.Â

KAKATA, Margibi – In May 2014, the Peace Corps gathered two dozen students from public schools across Liberia to participate in Liberia’s first post-civil war national science fair. The Peace Corps Liberia National Science Fair was designed for Liberian students to become exposed to scientific literacy and inquiry through presenting their research in both poster and PowerPoint formats. As Peace Corps teachers, we recognized that most students may never get the chance to carry out a science experiment and present it to a scientific audience. The science fair gave Liberia’s brightest students this very opportunity.

Student projects each explored one of the three themes: technology, health, or the environment. After selecting topics, participants learned and applied the scientific method. With the guidance of Peace Corps teachers or mentors, students developed hypotheses, conducted experiments and analyzed results, drawing conclusions of high relevance to their communities, Liberia, and other Sub-Saharan nations.

Popular topics included malaria prevention and treatment practices, community water source inspection, soil fertility analysis, and community health practices, such as bush medicine versus clinical treatment. Biofuel development, standard fuel efficiency and the processes of the brain were also investigated.

Each of the skills practiced in preparation for and during the science fair can be used to help develop Liberia. Scientific training and the associated critical thinking and problem-solving is more important for Liberia’s future leaders than ever before.

Throughout the fair, students demonstrated the growth of their inquiry skills through activity-centered group experiments and individual challenges. In addition, the students displayed unprecedented motivation and dedication to their intellectual endeavors, often working into the long hours of the night. Judges, mentors and Peace Corps staff were equally awe-struck.

The event’s success was made possible by the lead organizing Peace Corps volunteer, Tony Yang. Planning the event involved communicating with local educators, devising the event structure and student activities, and calculating resource needs such as poster materials, food and lodging for students. Fortunately, the Peace Corps Liberia staff was very helpful in supplying most resources and in supporting event preparation in every way.

Another significant aspect of designing the science fair was being realistic about what students could research with limited resources. Mentors played a crucial role in providing students with guidance and support. Communication among mentors was critical in setting realistic goals and challenges for our students as well as in ensuring that each student followed a standard format. This promoted greater understanding of the scientific method and showed students how to relate and communicate with peers about their conducted research.

The Peace Corps Liberia National Science Fair was conceptualized as an annual event. Peace Corps Liberia has every intention to continue the science fair, and even more, to expand it to more public schools and include more student teams per school. In the future, corporate sponsors may even provide scholarship prizes for the winners.

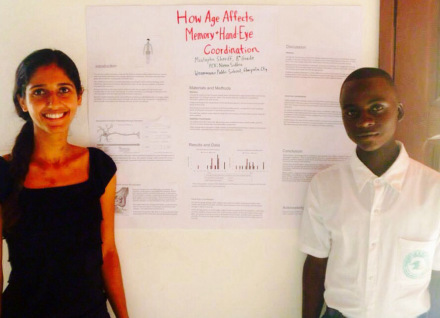

Mustapha Sheriff, then a student of Vaye Town Junior High School in Gbarpolu County, won the science fair. At the time 15-years-old and in the eighth grade, Mustapha was one of the youngest participants and without teammates. He presented his research project, “How Age Affects Memory and Hand-Eye Coordination,†to a room filled with competing peers, Peace Corps mentors, and three judges.

At the end of Mustapha’s 18-minute presentation, one of the judges and student leader of the Margibi Science Students Association, Musa Siryon, said, “I look forward to [Mustapha] becoming Liberia’s first and foremost neuroscientist.†This was less of an exaggeration than one might expect.

As his Math teacher, I recruited Mustapha to participate in the science fair. Early on, I had been taken with Mustapha’s uniquely inquisitive nature.

Mustapha compared two age groups in both memory performance and motor skills via hand-eye coordination. His subjects were asked to repeat complex new words immediately after the he introduced it, and one day after introduction.

He also timed them in threading a simple sewing needle. Mustapha then came up with explanations for the results that delved into the transmission of information between neurons, looking at multiple locations in the cell where information flow may be interrupted.

Yang commended Mustapha’s impressive handle on the science behind his topic as well as his command of the audience. As Yang presented the certificates and announced Mustapha as the winner, Mustapha’s reaction was a simple smile that completely concealed whether or not he expected it. It certainly was no surprise to anyone else present.

Featured image courtesy of Nimu Sidhu.