KAKATA, Margibi – It was in June of 2014 that the deadly Ebola virus entered Liberia for the first time, spurring an epidemic that killed 4,800 Liberians.

On June 28, in remembrance of health care workers who succumbed to the deadly virus, several partners in the health sector held a memorial program in Margibi to unveil a memorial for the 31 health workers who died from Ebola within the county.

The partners included the Liberia Center for Outcomes Research in Mental Health, also known as LiCORMH, in collaboration with the C.H. Rennie Hospital, the Margibi County Health Team, the Carter Center, and the Liberian Board for Nursing and Midwifery.

The epidemic prompted the government to order all bodies of people killed by the virus to be cremated after some communities refused to allow the burial of Ebola victims on their land.

However, that cremation, an unusual practice to Liberians, took a toll on a society already traumatized by Ebola as it denied communities a final farewell and led to standoffs with the Dead Body Management teams.

At night, mass cremations took place on the outskirts of Monrovia to minimize the impact on neighboring communities. Family members were not even allowed the ashes of their dead relatives and there was nothing physical left for them to commemorate the dead. Today, most of the victims do not have a grave site.

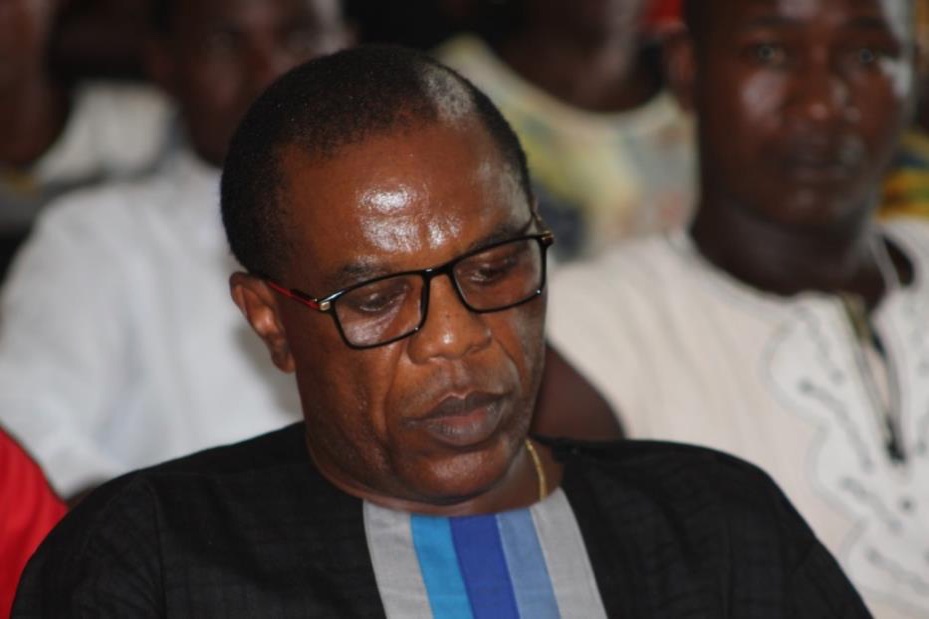

At the memorial ceremony, the former Margibi county health officer, Dr. Adolphus T. Yeiah, provided a historical reflection about the virus in Margibi, noting that the memorial program would contribute to healing the harm caused by the epidemic.

Yeiah now serves as the county health officer in Bong. At the time of the outbreak, he was the C.H. Rennie Hospital’s medical director while acting as county health officer.

“The Ebola outbreak was a traumatic experience,†he said, recounting that the entire health system in the county had collapsed.

Dr. Adolphus T. Yeiah, former Margibi county health officer. Photo: Zeze Ballah

During the outbreak, Yeiah said some of the hospital’s staff were infected and later died.

After the epidemic ended, Yeiah said the Margibi County Health Team felt that a memorial program was necessary to enhance the healing and psychological wellness of relatives of colleagues who succumbed to the virus.

The Ministry of Health, the Carter Center, and other partners decided to erect a marble stone for the fallen health care workers.

“The erection of the marble stone is going to serve as a giant step in remembering our colleagues,†he said.

“The health care workers deserve to be honored after their demise,†said Sehwah Sonkarlay, the executive directive of LiCORMH.

Sonkarlay welcomed the memorial on the compound of the hospital in remembrance of the county’s fallen health workers. He called for a national memorial to honor all health workers who died during the epidemic.

“The Ebola outbreak was one of the deadliest in our country’s history,†he added.

Sehwah Sonkalay, executive director of the Liberia Center for Outcomes Research in Mental Health. Photo: Zeze Ballah

Benedict Dossen, who recently took over as country representative of the Carter Center’s Mental Health Program, said his organization worked with LiCORMH to erect the memorial.

He said the Carter Center was honored to be part of the memorial for the country’s fallen heroes.

During the outbreak, Dossen said Liberia was completely vulnerable because of the lack of logistics to fight the deadly disease. He noted that “Liberians had little or no knowledge about what the disease was and how to deal with it,†rendering the country ill-prepared to fight the disease.

Despite this situation, Dossen said Liberia’s health care workers did not back off from the challenge.

Benedict Dossen, the new country representative for the Carter Center Mental Health Program. Photo: Zeze Ballah

“Despite the misconceptions about what Liberians were experiencing, the fallen health care workers fought to preserve the lives of families, and love ones,†he said.

“Liberians owe a lot to the fallen health care workers because they fought when there was a serious lack of trust and suspicion about the virus in many communities across the country.â€

Liberia’s chief medical officer, Dr. Francis Kateh, said the unveiling of the marble stone, which contains the names of the fallen health workers, was historic.

Kateh, who admitted that the epidemic “brought me to prominence,†told health workers to take pride in their colleagues’ contributions: “Today is not a day to cry, but rather a day to look at Liberia as a country where we came from and going.â€

Kateh recalled that in 2014, he was asked to go to the C.H. Rennie Hospital, where he and others spent several hours strategizing how to fight the disease.

Dr. Francis Kateh, Liberia’s chief medical officer, came to prominence as a national figure during the Ebola outbreak. Photo: Zeze Ballah

Kateh called for a reflection on the individual workers and to look to the possibility of a future resilient health care system.

“If Liberians continue to build on the possible things that gravitated us to the profession, the health care system can be changed,†he said.

A representative from the Serious Communicable Disease Program at Emory University in Atlanta, in the U.S., said he and his team were honored to be part of the memorial program.

Dr. Bruce Ribner said he and his colleagues were in the country to celebrate the lessons learned about managing the virus and to also celebrate those who did not survive the outbreak.

“At the beginning of the outbreak, there was a high rate of fatality and statistics,†he said, but he noted that fatality rates were much lower when the outbreak was declared over.

Dr. Janice Cooper (right), the former country representative for the Carter Center Mental Health Program, consoles the relative of a fallen health worker. Photo: Zeze Ballah

The first confirmed case of Ebola in Margibi was in June 2014. It later was transferred to the C.H. Rennie Hospital from the Kakata Rural Teachers’ Training Institute after it was discovered that the patient was suffering from weakness, vomiting, and fever.

Featured photo by Zeze Ballah