Joseph Boakai’s tenure as vice president of Liberia has been relatively quiet, particularly when considering the attention lavished on the president in whose administration he serves.

However, with barely two months remaining before national elections, Boakai appears to be in pole position to succeed his high-profile boss.

When The Bush Chicken asked me to review a biography of Boakai, I eagerly accepted as I was anxious to learn more about one of Liberia’s leading presidential candidates. I was concerned, however, that the book, published last year amid Boakai’s presidential run, would suffer from a lack of impartiality.

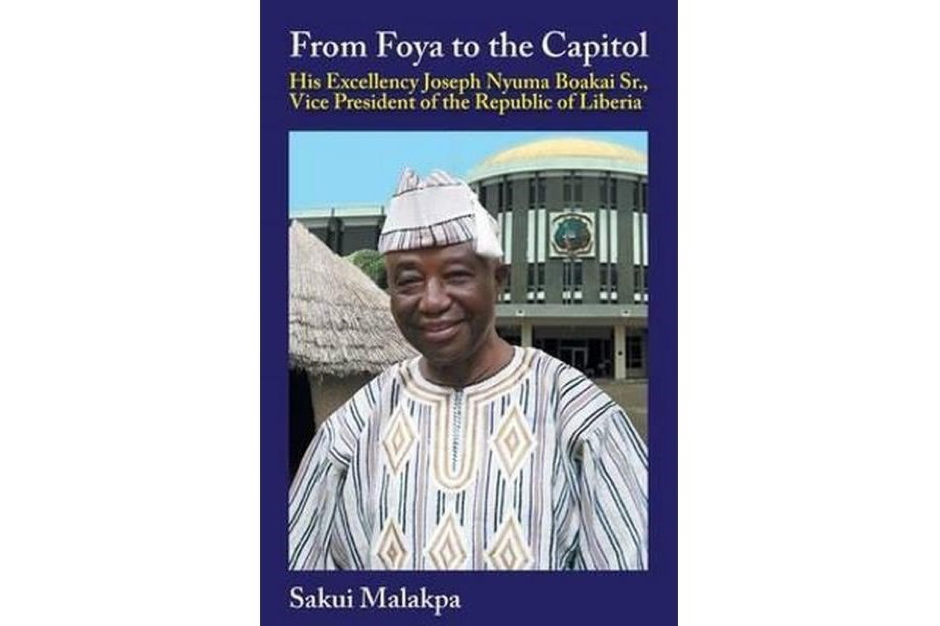

After wading through Sakui Malakpa’s 199 pages of didactic, fawning prose in From Foya to the Capitol, I now know considerably more about the politician who stands a good chance of becoming Liberia’s 25th president. The authorized biography draws on a number of interviews with Boakai himself as well as 60 interviews with family members and colleagues. Former President Samuel K. Doe’s one-time confidant George Boley is arguably the most interesting of the group.

Unfortunately, this new knowledge is tempered by Malakpa’s adulation of Boakai. The author, who holds two degrees from Harvard University, esteems Boakai as a “phenomenal†and “extraordinary man†and states that in the course of research “we were unable to get negative input about the VP, and we tried.â€

Malakpa, like Boakai, hails from Lofa and has also scaled impressive heights, overcoming blindness to become a tenured professor of education at the University of Toledo in the U.S.

Malakpa is at his strongest in recounting Boakai’s youth, detailing Boakai’s rise from a clumsy child laborer taking an accidental ‘latex bath’ on the Firestone rubber plantation to a graduate of the University of Liberia’s class of 1972. While the author’s prose is sycophantic to the extreme, the overall portrayal of Boakai’s dramatic rise as a result of his singular determination is convincing.

From abusive uncles (and a malevolent aunt who served him food in a chamber pot) to a sick mother and absentee father, Boakai’s early life was marked by his relentless struggle to obtain an education in the face of numerous obstacles. While the septuagenarian’s age may cause some to question his connection to the Liberian populace, his inspirational story will speak to the many Liberians who see education and hard work as a pathway to success.

In recounting Boakai’s early years, Malakpa reveals a number of anecdotes that will be of interest to historians, anthropologists, gossipers, and followers of Liberian politics. These include a Liberian uncle who served with British forces in World War II, the impressively late closing time of the Rivoli Cinema on Broad Street (Boakai was once an employee and clocked off at 3 a.m.), and his abbreviated dates in Bomi Hills with his first girlfriend, Comfort Johnson.

Malakpa spends a not inconsiderable amount of time on Boakai’s experience as a high school student and employee of the College of West Africa, which the author notes was highly formative. Indeed, as a senior student at CWA, Boakai got his first taste of political success, defeating John Richardson, a future minister of public works, for the student council presidency by just one vote.

Once Boakai gets his first taste of professional success, employment following graduation with the Liberia Produce Marketing Corporation, Malakpa’s platitudes (“the journey of life is laden with hills and valleys, setbacks and successesâ€) and praise singing of Boakai begin to require more patience than a reader is inclined to exhibit.

The reader that endures will be disappointed that Boakai’s tenure as vice president receives no consideration – although allegations that he sleeps during meetings are briefly refuted. The final three chapters on Boakai’s ‘uniqueness’ are particularly obsequious. Section headings would not be out of place in a Boakai campaign manifesto – ‘VP Boakai Manifests Genuine Patriotism, ‘VP Boakai Displays Consummate Leadership Ability,’ etc.

The work also teases with a number of passing references that would benefit from further exploration. Malakpa devotes just two sentences to what appears to be Boakai’s first trip to the U.S., a 1976 visit facilitated by a fellowship at Kansas State University (Boakai later lived in Washington, D.C. in the mid-1980s). Boakai’s self-imposed exile after he was fired by Doe in 1985 warrants only a brief mention, as does his decision to return to Liberia and start his own business in 1988.

Malakpa notes several instances of Boakai standing up to corruption in Doe’s government, but does not reflect on the ways in which Boakai’s service in the military government reflects on his democratic credentials. It is also implied that before he fell out of favor with the master sergeant, Boakai was desirous of being named Doe’s running mate in the 1985 elections that sought to legitimize the government that came to power via a bloody coup.

The interesting anecdotes become less numerous as Boakai’s career progresses, although Malakpa intriguingly insinuates that Boakai’s role as president of the Movement for the Protection of Liberian Interests (the mandate of this organization is not explained) caused friction with interim head of state, Amos Sawyer, in the early 1990s.

One of the most interesting, but incidental takeaways from the book is Boakai’s pan-African grounding. Before the war, he had lived in both Ghana and Sierra Leone, earning a management certificate in the former and learning both Mende and Krio in the latter. During the war, as a result of economic upheavals, he embarked on consultancies in Uganda and Tanzania and briefly resided again in Sierra Leone.

Malakpa’s effusive praise of his subject makes it difficult for a discerning reader to ascertain what a potential Boakai presidency may be like. A penchant for a liberal application of quotes from luminaries ranging from the American comedian Michael J. Fox to the ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius to buttress his points about Boakai’s sterling character further complicates this effort.

If elected, Boakai would have a significantly different profile from that of his predecessors. For the most part, this should be a positive attribute. However, From Foya to the Capitol reveals that while Boakai is a self-made man, his making was shaped by external influences.

Among others, Malakpa draws on interviews with a former Peace Corps volunteer and a Lebanese businessman who have each known the VP for decades. While Malakpa is at pains to portray a genuinely principled man, the picture that emerges is of a pious individual who values relationships and seeks to uphold his principles within the parameters of existing networks and norms rather than to dramatically confront the status quo in the face of injustice.

However, the same was said of another religious VP and University of Liberia graduate, William Tolbert, who upon ascension to office unexpectedly made a mark as a reformer. The coming months will tell if the most important chapters of Boakai’s tenure at the Capitol are yet to be written.

Featured photo by Africana Homestead Legacy Publishers