Grow up. Become a soccer star. The typical Liberian boy aspires to reach these two milestones.

Before heading to Rio, Liberia’s track team coach, Sayon Cooper sat in his office at the Morehouse School of Medicine and reflected on how his soccer dreams turned into track and field success.

“I didn’t know anything about going to college for free on a track scholarship,†Cooper admits.

His track career began, almost accidentally, during the end of his sophomore soccer season. Sayon’s high school soccer coach insisted he find a way to stay in shape until the new season began.  That summer, Coach Godrey Moore, transformed Sayon from a striker into a sprinter. In 1992, His undeniable speed got him lots of attention at Seneca Valley High School. It had only been a few years since the teenager left his grandmother in Liberia to join his parents and younger siblings in Maryland, USA.

Cooper confesses, “I wanted to be like my father. He played soccer, but not professionally.†Instead, the young runner took on his mother’s athleticism. “My mother ran track and played basketball. She was very good,â€Â he adds.

Indeed, his mother’s athletic genes opened huge doors.

“First my high school coach told me I could go to college for free. So, I set my goals on that. Then my college coach [1956 men’s 400m hurdles Olympic Bronze medalist Joshua Culbreath] told me I was good enough for the Olympics. So I set my goals on that,†Cooper explains.

He leans back in his chair and laughs at how clueless he was about his talent and the opportunities it would provide. As Cooper continues the conversation, he subconsciously runs through a list of names — coaches and agents who impacted his career. Coach Culbreath. Coach Kitley. Paul Doyle. Coach Seagraves. The list goes on.

Each name acts as an investor contributing to Cooper’s impressive accomplishments at Central State University, Abilene Christian University, two Olympics, and several world championships.

Out of these experiences, he lingers on the 1996 Olympics.

“Liberia was going through a war, and I was proud to represent my country. I was proud to show that there was still hope for us,†Cooper recalls.

The 1996 Liberian Olympic team came together, during a time when death and war were the only images coming from Liberia. Five total athletes competed. All of them were star runners, born in Liberia and living in the US. They dashed into Atlanta’s Olympic Stadium during the opening ceremony, dressed in all white waving their hands, pumping their fists, chanting, and smiling behind Liberia’s bold star and familiar stripes. Thousands of displaced Liberians around the world watched. For the first time in many years, they could see their country and smile. This is one of Cooper’s most memorable moments.

From this point on, Cooper represented Liberia in national competitions. Running for his country was rewarding, but after 13 years of fierce competition, Cooper retired from the sport.

He ran his last race in 2005.

Cooper stayed away from track for four years, but colleagues pressured him to return and he complied.

“When you have a calling, God has a way of pulling you towards it,†Cooper says. I’ve always wanted to expose athletes to the information and opportunities that my coaches gave me.â€

Since 2011, Cooper has coached the Liberian Track Team. He also coaches the fastest girl in the world— Candice Hill — with Tony Carpenter. In addition to building superior athletes, Cooper has taken on the mission of building superior coaches.

“I would like to host a coaching clinic in Liberia,†Cooper shares.

He smiles as he explains how important it is to understand the mental and physical aspects of the sport. It is important for coaches to get in the blocks and show the athletes how to perform, but poor coaching is not Liberia’s only problem. With an irritated sigh, Cooper states his concerns about the inadequate track that outlines the Samuel Kanyon Doe Sports Stadium in Liberia. The track has its good days, but regular maintenance has been an ongoing problem.

Qualified Liberian coaches,  a proper track, and overall support are key factors in maintaining and improving the standards that Cooper has set for Liberian runners. These changes will allow Liberia to identify and groom talented athletes.

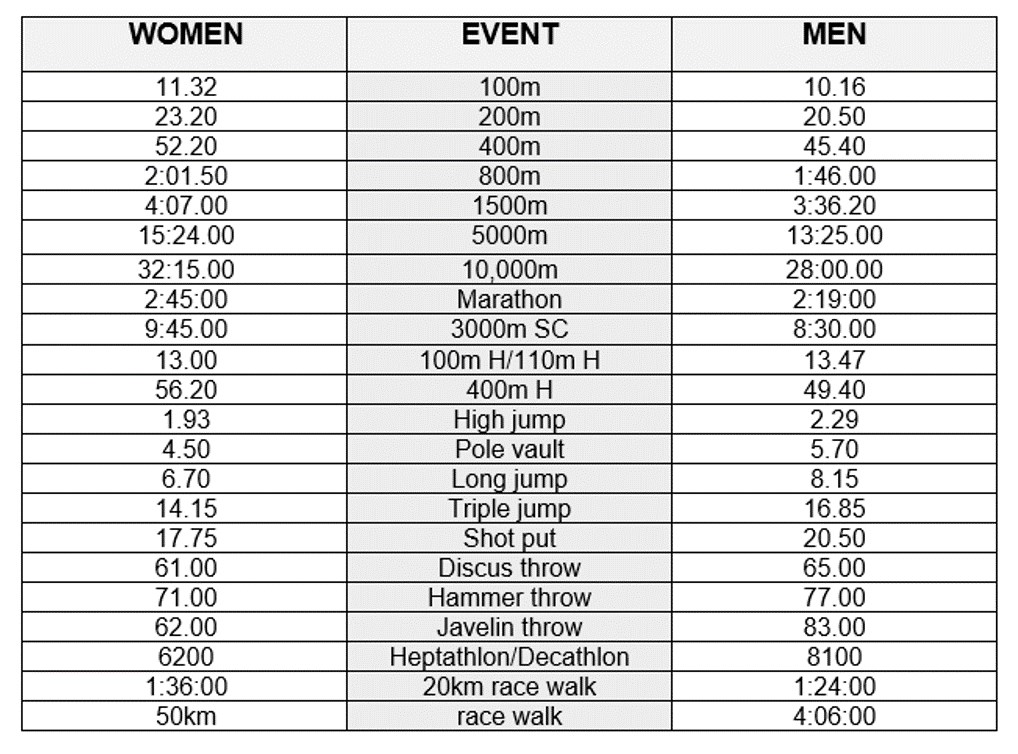

“We do not send quota athletes to the Olympics. All Liberian track members must qualify†he says.

2016 Olympic Entry Standards.

Cooper acknowledges the problems that still exists and is prepared to tackle the issues. Between coaching and managing the Public Health Program at Morehouse School of Medicine, it seems Cooper has his plate full. However, he always leaves room for his favorite thing— his enormous family.  Cooper takes time to mention his three daughters; his fiancée and her two daughters; his parents and step-parents; his brothers and sisters; in addition to other extended family members. He says they are his relief.

“I believe that I can have it all— family, my public health career, coaching, and anything else God blesses me with.â€

This article originally appeared in the Liberian Olympic Blog. Featured photo courtesy of Sayon Cooper.