A report of the High-Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa revealed that Africa loses on average US$50 billion every year to illicit financial flows, more than the total sum of development aid the continent receives annually.

Illegal financial flow is money illegally earned, transferred, or utilized. A presentation on the report argues that the major sources of illicit financial flow range from commercial tax evasion, criminal activities and bribery, and theft by corrupt government officials. Recovery of or prevention of these outflows could largely improve many sectors across the continent, including education, health, and transport.

Over 150 youth leaders, civil society leaders, government officials, diplomats, and heads of state convened during the week of November 26 in Gaborone, Botswana to discuss the transformational future of Africa through the lens of a corruption-free continent.

Two events – the 2018 Gender Pre-Forum on Women’s Rights and Corruption and the High-Level Dialogue on Corruption – were organized by the African Governance Architecture, an African Union platform aimed at promoting good governance and strengthening democracy in Africa.

A significant impediment to development and sustained growth on the continent, corruption has long been a major discussion across the continent. Africa’s leaders recognize that their past efforts have not achieved the desired results in curbing corruption and they are designing new approaches to intervene.

Over the past few years, the African Union has proposed several tools to tackle and reduce corruption for the greater good of its citizens and the development of the continent: the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights, African Union Declaration on the Principles Governing Democratic Elections in Africa, Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption, AU Advisory Board on Corruption, and the African Peer Review Mechanism. Yet, despite these efforts, the lack of political will across the continent means that corruption remains Africa’s biggest problem.

Besides the various anti-corruption tools set up by the African Union, every country has a well-defined anti-corruption institution with customized laws to aid in the fight against corruption. These institutions, however, require the support of the heads of state and parliament to ensure they succeed.

Sierra Leone, for example, has seen significant progress against corruption over the last 10 months. In his discussion on the political governance of Africa, Sierra Leone’s Anti-Corruption Commissioner, Francis Kaifala, noted that “Sierra Leone has one of the strongest anti-corruption laws in Africa, but good laws alone are not enough.â€

Kaifala’s strategy to address corruption goes beyond exposure or naming and shaming. It also involves prosecution and the recovery of stolen resources – an approach he coined as a “good anti-corruption campaign.†Under his leadership, the commission has retrieved about 10 billion Leones (US$1 million) in only about five months – greater than what was recovered in the last 18 years combined.

It is important to note, however, that all this is possible because of the support from the president and other so-called integrity institutions. The estimated timeframe where the fight is active is the first 18 to 24 months when leaders are most serious about delivering on their commitments.

After that time, more focus is placed on strategizing on how to maintain leadership for the following term. Potentially corrupt activities then become less frequently monitored and evaluated, and there is limited support from the head of state or parliament.

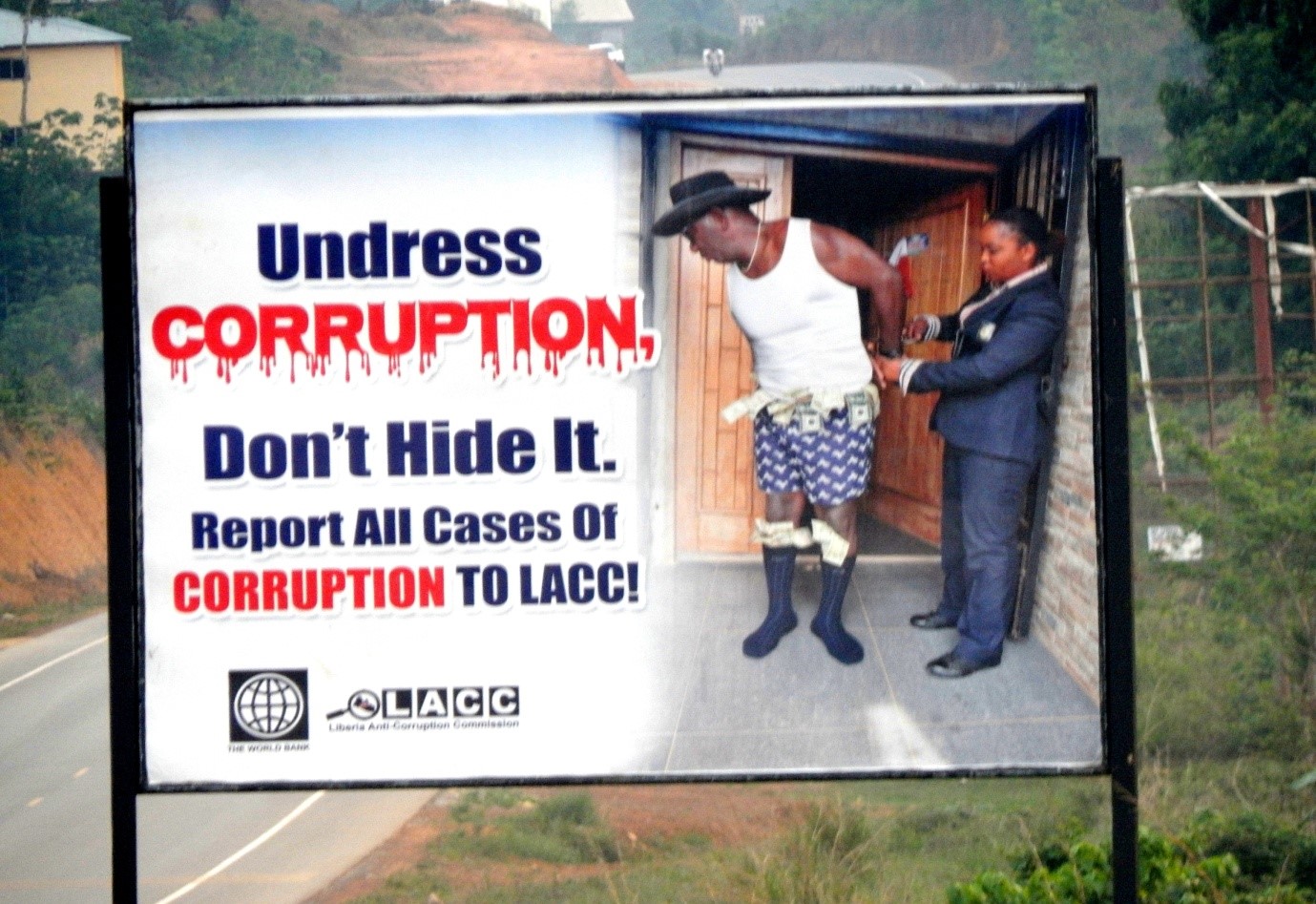

Liberia, for example, falls within this optimal timeframe for fighting corruption. Like Sierra Leone, Liberia experienced the induction of a new government within the past 12 months. However, not much has been done by the Liberia Anti-Corruption Commission to investigate the corruption of the previous and current government, prosecute perpetrators, and, on a deeper level, recover stolen funds.

Numerous cases of corruption have been highlighted over the last months, including a few involving the president, but no action has been taken to resolve the matters. As the government will turn one-year-old in January 2019, there is still an opportunity to ensure they achieve on this commitment of tackling corruption, as promised by the president.

These reasons and more validate that winning the fight against corruption requires more than good laws and instruments – it also requires decent leaders with good behavior. While we maintain existing instruments and develop new interventions to address corruption in Africa, if we as individuals can also practice what we seek to achieve, our fight against corruption to give Africa a transformation can be now, or if not, not yet.

Featured photo by Arrington Ballah