When I began my master’s in history at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London in 2015, my intention was to focus on the nexus between African religions and warfare in Kenya (Mau Mau) and other similar insurgent groups during the 20th century.

It was not my objective to solely focus on Liberia’s history, but that changed during my orientation when one of the university’s history professors suggested that I focus on Liberian history instead.

I am now a doctoral candidate in History at the same university studying critical aspects of Liberia’s and Sierra Leone’s 19th century cultural past. As my professor stated, there was not much originating out of Liberia academically because of the country’s troubled past.

Following his advice, I wrote my thesis on the cultural and religious aspects of the First Liberian Civil War, which began in 1989 and ended in 1997.

Since my Masters of Arts orientation, Carl Patrick Burrowes’ manuscript entitled Between the Kola Forest and the Salty Sea was published in 2016. In this study, Burrowes examines Liberia’s history before 1800.

This is significant because it is often implicitly assumed that the country’s history began in 1822 with the arrival of the African American settlers when in reality, the history of the region prior to 1822 is as vivid and dynamic as it was after 1822.

Burrowes informs us that Liberia’s past is deeply connected to that of the ancient Mali empire (13th to 16th century) through Mande migration in the 16th century.

Interestingly, a few years ago I had a conversation with a close family member about the Malian king Sundiata Keita, whose story this individual informed me was taught through oral traditions as a child in Cape Mount.

At the time, I asked myself why someone in Liberia be exposed to Malian oral tradition. By learning about Liberia’s 16th-century history, I now understand why.

With that stated, what is needed is a concentrated revival in the study of Liberia’s past. What is needed is a new generation of professionally trained Liberian historians who can furthermore expound on the research begun by scholars in the 1960s.

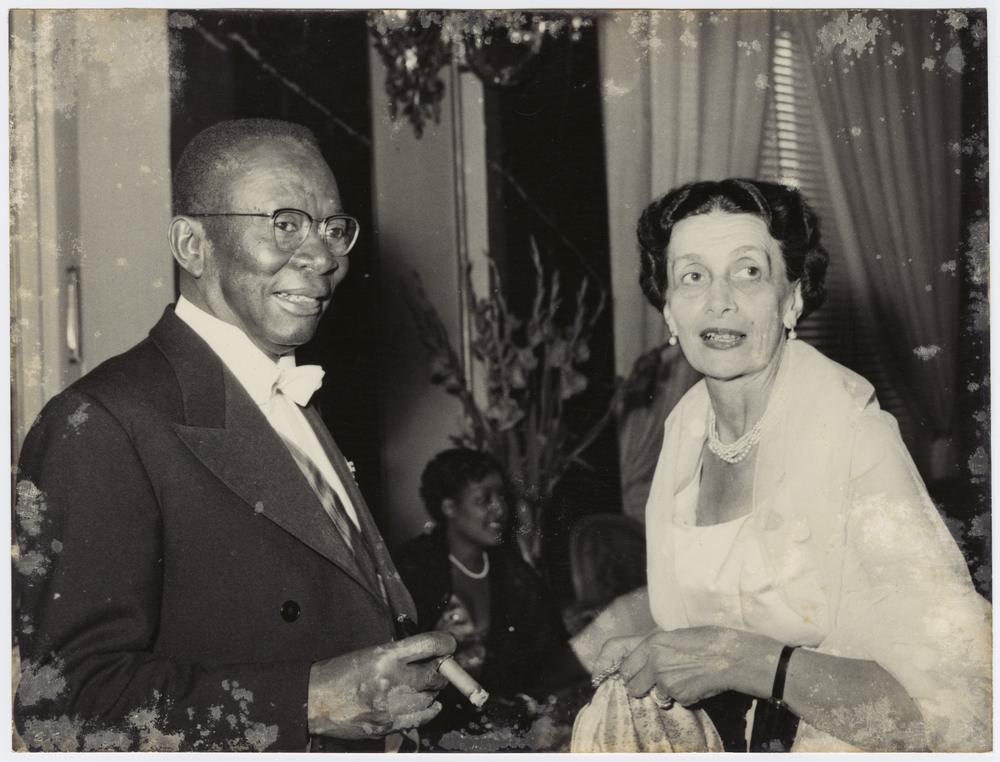

It is without a doubt that Liberians owe gratitude to Joseph Saye Guannu, Abeodu Jones, Elwood Dunn, Monday Akpan, Mary Moran, Carl Patrick Burrowes, Warren d’Azevedo, Svend Holsoe, Alpha Bah, and other academics who pioneered the study of Liberia’s past. Unfortunately, some of the scholars of that generation including d’Azevedo, Holsoe, and Bah are no longer with us.

Others like Guannu and Dunn are trying to cultivate a new group of professionally trained Liberian historians to carry on the important work that needs to be done. Some of the areas of Liberia’s history that need critical study are gender relations, migration, and early military history.

In fact, in my conversation with Dunn before the start of my doctoral studies, he expressed this desire to me. More importantly, he promoted the idea that there should be a cross-disciplinary fellowship of professionally trained academics within this generation of Liberians.

To this end, he introduced me to Robtel Pailey who also earned her Ph.D. at the School of Oriental and African Studies. True to who she is, Pailey took me under her wing and has been a mentor who has encouraged me each step of the way. In turn, I have introduced her to newly-minted Liberian historian, Henryatta Ballah, who earned her doctorate from Ohio State University. Ballah’s focus is 19th-century Liberian history and she is currently teaching at Connecticut College.

Renewed interest in Liberia’s past began as a result of the First Liberian Civil War. Many of these studies were driven by outside perceptions of the civil war, its causes, and its impact on Liberian society.

Indeed, a veritable cottage industry emerged around the war, creating instant experts on Liberia. The work ranged from serious scholarships to the questionable. Unfortunately, many of these studies have distorted Liberia’s past due to the writer’s unfamiliarity with Liberia, Liberians, and the nuances of Liberian culture and history.

Isabelle Duyvesteyn’s Clausewitz and African War, in which she offers a comparative study of Somalia’s and Liberia’s conflicts through Clausewitz’s theories come to mind. In this example, the issue is not with the application of Clausewitz’s theories, but because Duyvesteyn acknowledged limitations in her work since the Second Liberian Civil War denied her the ability to conduct fieldwork there.

This, combined with her heavy reliance on secondary sources, created some questionable analysis. It is not to imply that non-Liberians are incapable of writing credible Liberian history – D’Azavedo, Holsoe, Akpan, Moran and Bah have demonstrated that this is possible. The issue is being able to recognize the quality of your sources.

This problem is not solely relegated to outsiders, it affects Liberians as well. Take the recent case of the award-winning Liberian New York Times reporter, Helene Cooper, who claimed that “Liberia’s next change in leadership will be the first instance of a post-presidency in Liberia’s history.â€

As Dunn has reminded us, this is not the case. Cooper has repeated this narrative on various media outlets in the U.S., creating an alternative version of Liberian political history that is not accurate. This problem is aggravated because as a well-known and accomplished journalist, Cooper’s assertion gains instant credibility.

Presently, it can be reasonably argued that Liberian history is understudied and misunderstood. There are some bright spots, as I mentioned, both Robtel Pailey and Henryatta Ballah have stepped up to fill this void. What is needed are more Liberians willing to undergo years of grueling academic training to become professionally trained historians.

Funding is also needed. In my experience, unless the project is related to violence or conflict, finding the funding to conduct research on other aspects of Liberian history is a challenge. It is an issue that I have faced and continue to endure, but I have the faith, however, to persevere. In two short years, I will join Ballah as a specialist of 19th-century Liberian history.