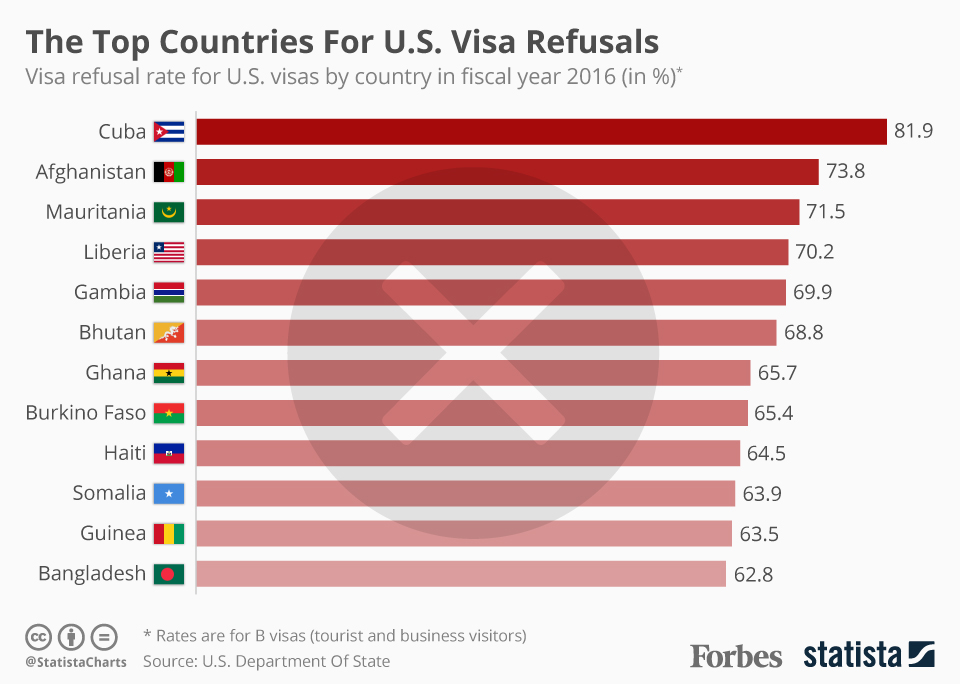

MONROVIA, Montserrado – Despite the closeness in diplomatic ties, Liberia has one of the highest US visa refusal rates. The country ranks fourth after Cuba, Afghanistan, and Mauritania.

Statistics from a US State Department website reveals that 70.2 percent of Liberians who applied for US visas for tourist and business purposes in 2016 were denied. Only 3,214 visas were approved out of a total of 10,796 applications.

Paul Hinshaw, the public affairs officer at the U.S. Embassy in Monrovia, wrote via email that there are many reasons why visa applications may get rejected. One reason could be that individuals may not qualify for the specific visa category for which they applied.

“In other cases, the applicant is inadmissible to the United States or ineligible for a visa because a previous visa was used improperly, or due to other actions the applicant may have taken in the past,” he wrote. “And, in many cases, an application requires additional processing before a visa can be issued. In all cases, whenever an applicant does not qualify for a visa, the interviewing officer provides a written explanation of the refusal to the applicant.”

In a previous communication, the U.S. Embassy’s Public Affairs Section had told The Bush Chicken that Liberia’s non-immigrant visa refusal rate is relatively high, compared to other countries.

“In fiscal year 2015, 12 percent of Liberian visiting visa holders overstayed their visas rather than departing the United States in a timely fashion,” an embassy spokesperson said.

However, Hinshaw clarified that it is inaccurate to say that travelers must leave the United States “before their visas expire,” as it is a common misperception on the time periods individuals on visas can stay for.

“You may stay in the States after your visa expires. The visa expiration date is the last date it can be used to apply for entry to the States, not the last date someone can be in the States,” he wrote.

The 12 percent of Liberians who were overstaying their tourist or business visas were likely staying much longer than the usual six months provided for a visa carrier.

Hinshaw said it is unfortunate that some Liberian travelers stay in the US longer than permitted, as that makes it more difficult for future Liberians applying for visas.

“When we see this, new visa applicants face a higher burden of proof to demonstrate their intent to use a visa appropriately,” he wrote.

At a rate of US$160 per application, the embassy made US$1.73 million from visitors’ visa applications last year.

Asked about any guilt on the part of the embassy for profiting off mostly poor applicants, Hinshaw said U.S. law requires the Department of State to attempt to recover, as far as possible, the cost of processing non-immigrant visas through the collection of the application fees.

“We note that the fee for a multiple-entry, one year B1/B2 (visitor) visa to the United States is currently US$160, while the fee for a multiple-entry, one-year visitor’s visa to Liberia is US$200,” he continued.

Although the embassy’s defense that American citizens coming to Liberia are charged a higher amount than what it is charging in Liberia, it did not account for the significant differences in earnings. The average Liberian earns approximately 300 times less salary than the average American.

To the embassy’s credit, there is enough information on its website to provide clarity to potential visa applicants. Hinshaw said U.S. immigration law requires the embassy to err on the side of caution in ensuring that visitors are not actually intending immigrants.

“At the same time, we make sure that our website reflects accurate, up-to-date information, so that applicants can make informed judgments ahead of time as to whether or not they will qualify for a given visa classification,” he noted.

Hinshaw said there is no ideal visitor other than one who has demonstrated that he or she has the means and intent to use a visa appropriately and return to his or her home country in a timely manner.

Outside the embassy, Liberians waiting on their visa applications refused to speak out of fear of jeopardizing their chances at being given a visa.

Elsewhere in the city, some Liberians have expressed shock over the high refusal rate of citizens who attempt to travel to the U.S. as visitors.

Ishmael Taylor, a government worker, told The Bush Chicken that the number of people being rejected access to visiting visas in Liberia is discouraging to others who might want to visit the U.S.

“I think there is a need for the government of the U.S. to revisit its immigration policy on Liberia,” Taylor said.

Pinky Carr, a local businesswoman, said the high rate of US visa refusal on Liberian citizens jeopardizes the long historic diplomatic relationship between both countries.

Carr said the long history between Liberia and the U.S. makes it crucial for the U.S. government to relax some of its policies on Liberians wanting to visit the U.S.

“In most places around the world, people consider Liberia as small America, but the way Liberian citizens’ visit to the U.S. is limited contradicts what people outside of Liberia think of both countries,” she added.

Liberia became Africa’s first independent republic in 1847 from the United States of America. The American Colonization Society first colonized the country in 1822 as a home for freed slaves from America. Liberia was under the colony of the ACS until 1839 when it entered a commonwealth rule.

Since then, both countries have enjoyed a long history of diplomatic relations, with the U.S. being considered the preferred second home for most Liberians.

Featured photo by Forbes