Much of what is occurring in Liberia today is very evocative of the period between 1869 and 1872. The 1869 election pitted the Republicans against the newly formed and insurgent (True) Whigs. Liberia was still a fairly new experiment, but a marvel in terms of black governance. The Republicans had been in power for 22 years. As always, parties that stay long in power tend to become entrenched and detached from reality.

The Whigs, on the other hand, were a grassroots party anchored to the changing demographics of 19th century Liberia. The Whigs defeated the Republicans in a hard-fought election that saw the democratic revolt of the people against the political establishment, albeit the result produced a divided government.

On the same ballot that brought the Whigs to power were several amendments to the Liberian constitution to extend the terms of office of the president and legislature. The amendments passed in a landslide, supposedly because both sides expected to be on top. When Roye and the Whigs came out on top, the Republicans balked. The result of the amendments was never certified and the amendments were placed on the ballot on a new referendum in 1871.

The result of the second referendum was never counted “publicly,” while the Senate seized the ballot and declared via a resolution that the amendments did not receive the two-thirds majority needed for passage. What followed was a period of accusations and counter-accusations, which culminated in civil unrest and the eventual toppling of E.J. Roye and the Whigs.

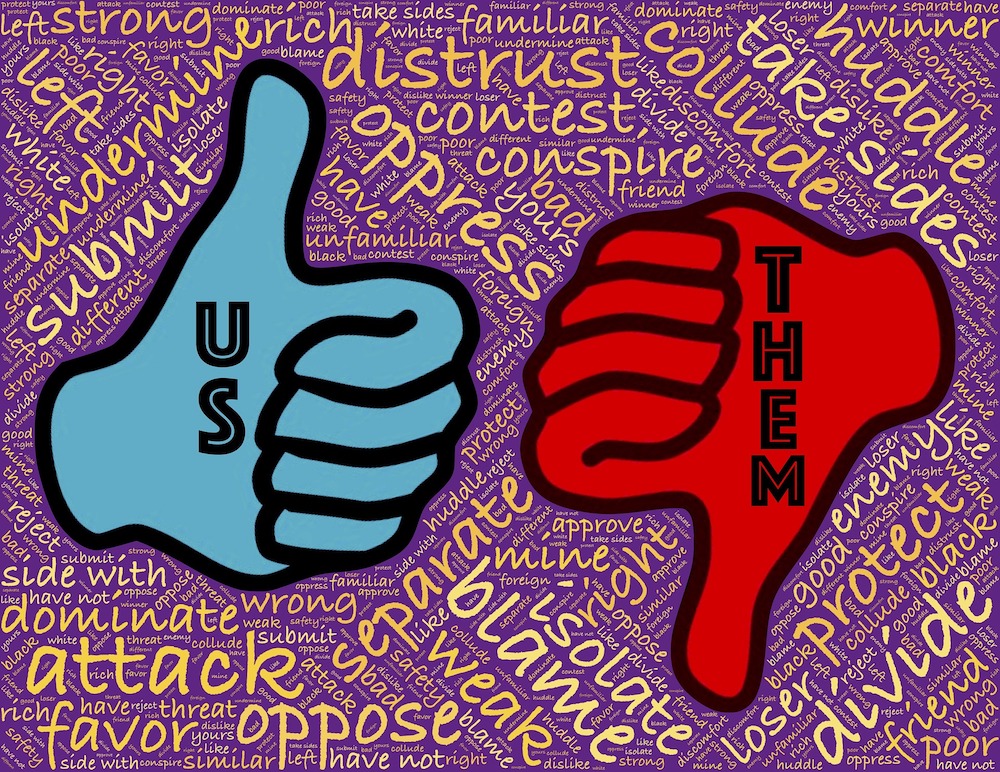

The Republicans violated a cardinal democratic concept in deposing Roye and the Whigs – a concept first espoused by the British parliamentarian John Hobhouse in 1826: the Loyal Opposition. This means that regardless of “whoever holds power, all sides must respect the fundamental legitimacy of their political rivals.”

Differences of opinions on policy matters should not be seen as treasonous nor out of bounds, but rather as spirited disagreements within a divided and adversarial system of government, which as a whole retains ultimate authority.

What that means in actuality is meeting the other side face-to-face in a battle of ideas or policy alternatives. Respecting the others’ right to promote their point of view and admit that winning the debate means mounting the superior argument, using sounder reasoning, marshaling compelling evidence. It means not attempting shortcuts to victory by delegitimizing the other side, even before the debate, or villainizing an opponent, or deploying alarmist rhetoric.

We abandon genuine debate when we contend that those with different political persuasions are not just wrong, but are inherently bad, even to the point of alleged criminality. The loyal opposition must always argue that the other side’s conclusion or policy prescriptions are due to faulty logic or evidence, and not mere ill will. They must go beyond rants by offering serious and constructive policy alternatives to the status quo, all the while galvanizing the people and building a more vibrant coalition for the sole purpose of winning elections.

What the Republicans did in 1871 was undemocratic and extra-constitutional. The deposition of President Roye was a precedent future generation of Liberians under the banner of the erstwhile National Patriotic Front of Liberia and now the Council of Patriots will exploit to usurp the popular will of the Liberian people.

Democracy only works well when we all adhere to the rules. “The loyal opposition” must get in the habit of winning election as a means of counter-balancing the excesses of the status quo.

Featured photo courtesy of John Hain