Liberian political commentators are in abundance in this day and age, but few are writing books that Liberians must read.

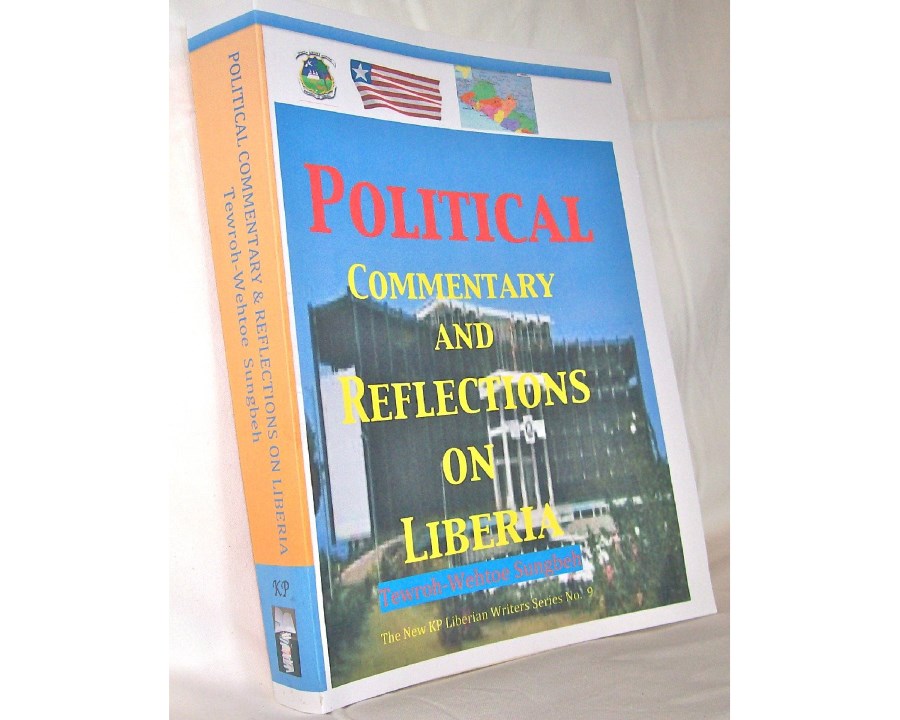

Telling the history of a troubled nation as it gravitates from one crisis to another is an important national milestone, and that is why Tewroh-Wehtoe Sungbeh, the editor and publisher of the provocative Liberian Dialogue website, deserves commendation for his book, Political Commentary and Reflections on Liberia.

This is not just a recorded history meant for libraries and students, but for all of us. The book takes into account Liberia’s political events from 1980 to 2014. This is a decade and a half of turmoil told in no mincing words from a critic whose passion for this country brings relevancy due to his long time advocacy for the rights of the Liberian people.

The book is a thick volume. Its detailed narration documents the violent military overthrow in 1980 of an oligarchy, precipitated by the settler class’s grip on power and the hegemonic rule of the True Whig Party, which ruled the country for 133 years.

The book also discusses Liberia’s military coup and the so-called People Redemption Council’s misrule. Consumed and overwhelmed with the trappings of power, it soon becomes dictatorial under Master Sergeant Samuel Doe. Sungbeh ends with Taylor’s war and his historical butchering of a nation, which led to the election of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf as Liberia and Africa’s first democratically elected female president. Included in his commentary is his notice of the patronage, impunity and massive corruption under Sirleaf’s watch. Political Commentary and Reflection speaks truth to power, and Sungbeh is erudite in his analysis and observations.

Sungbeh’s 385-page chronicle is worth the read. He writes passionately about Liberian democracy in the context of preserving the tenets of institution-building by upholding the rule of law while decentralizing political power and taming the historical powers of the almighty imperial presidency. He notes that this reckless abuse of state power is the singular cause for power grab in the country and Liberia’s descent into chaos and confusion in the preceding years.

He opined that since Liberian presidents have always used unbridled power to consolidate authority and influence by divvying up patronage to the brown-nosers who cater to their whims, something radical must be done to correct this historical malaise. He also wrote that less can be achieved when the Liberian legislature does not know what to do with its powers, as it often kowtows to the executive.

For example, Sungbeh wrote, “it is one thing to admire…a sitting president for what he or she brings to the political table in the interest of the country. However, it is one thing to prostitute one’s convictions by ignoring the troubling flaws and wanton abuse of power of a president.†Being the activist writer he is, he continued, “this is not only a sellout, but it is recklessly adventurous and dangerous.†The book is a thought-provoking recipe for drastic change meant to grow the body politic.

Consequently, for a book that has historical subtexts and perspectives, its bibliography and references are diminutive. The book could have been better referenced by using adequate indexes most especially to make for easy research purposes. Tewroh-Wehtoe Sungbeh has written a good book, however.

Political Commentary and Reflection on Liberia is a timely critique. But while the admonitions are hefty, it would have done well to provide some clarifications to the myriad snags of Africa’s first republic. But then again, in these narrations, perhaps the writer admonishes his audience and readers to draw conclusions and corollaries from his analysis and pontifications. Sungbeh acts as a mirror to see what’s wrong with a patronage system and then derive answers.

Political Commentary and Reflection on Liberia, published by Kilton Press, a Liberian owned publication located in Rhode Island in the US, is available for purchase here.Â