In reaction to recent debates surrounding the legacy of Liberia’s 19th president, William V. S. Tubman, an elderly Liberian woman remarked to the effect that today’s Liberia is Tubman’s Liberia – that we’re living in Tubman’s shadows.

To Tubman’s many critics, such sentiments may reflect the nostalgia felt by a passing generation still relishing the ‘good old’ halcyon days of national glee and street festivities. But the old woman’s observations could not be more accurate. They are a profound reflection of not only the broadly positive view about Tubman held by many older Liberians (according to a recent study by Timothy Nevin), but also about Tubman’s larger-than-life influence upon the Liberian society some 50 years after his passing in July 1971.

More monuments and edifices stand in Tubman’s honor than there are universities in Liberia. Owing to his administration’s fiscal fortunes, Tubman poured more steel, asphalt, and cement into Liberia’s built environment, than all his predecessors combined – creating new cities, highways, hospitals, schools, universities, water purification plants, sewage systems, hydro-electric plants, ports and port extensions, bridges, airports, etc.

The evidence of infrastructural dispersal shows that these developments were not limited to his home county of Maryland, as some critics have suggested, but were scattered across the country. On the continental and global levels, he was a force of consequence. His convivial personal diplomacy helped etched an indelible imprint on African and world politics in ways that were only recently approximated by former President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf.

The old woman’s comments also echo the uncomfortable reality that 50 years following his death, very little in the way of national progress has occurred in Liberia. Except for the broader economic consolidations witnessed during the Tolbert presidency (1971-1980), post-1980 Liberia has been a monumental national failure. Though inexplicit, the old lady’s comments are a biting critique of post-Tubmanic generations of leaders. And yet surprisingly, President Tubman’s legacy remains largely underappreciated; shrouded in myths, mysteries, half-truths, and fantastical claims of dictatorship and totalitarianism. It remains fiercely contested by scholars and historians of the Liberian and African experiences.

In fact, Tubman’s administration stands broadly criticized in contemporary narratives as grossly incompetent, underachieving, and perhaps the most destructive force in Liberia’s democratic evolution. The question I now ask is: Why such a negative portrayal?

As a young student leader and activist growing up in Liberia, I harbored similar broad criticisms of the Tubman presidency. Regaled by tales of indigenous struggles against emigrant paramountcy and dazzled by accounts of Liberia’s “progressive” intellectuals’ fight for multi-party democracy (and against Americo-Liberian single-party rule), I also voiced similar disdain against President Tubman. But as I examined primary records of the Tubman era in the course of my doctoral research (2015-2019), I became puzzled by the dominant critical view of the period, and about the man and his administration.

My Ph.D. research focused on the central role rent revenue (i.e., massive revenue inflow from resource exports) played in the dynamic processes of Liberia’s post-WWII state and nation-building. But as I deep delved into the primary evidence, I soon become disillusioned by this dominant critical narrative, and to question it. I have come to the conclusion that the contemporary portrait of the Tubman era (and of the man himself) deserves a serious rethinking, if not an entirely new fresco.

The basic argument I make in this two-part essay is that, in order to fully understand and appreciate President Tubman’s legacy, one must go beyond a simple assessment of his fraught relationship with opposition politics, and the binary categories of ‘settlers v. indigenes,’ ‘Americo-Liberian v. indigenous,’ ‘Country v. Congo,’ or ‘liberal v. illiberal’ democracy. These narrow lenses tend to obscure our understanding of the deeper and more complex dimensions of the political, social, and economic processes underway during the period.

Instead, we must adopt a more thematic and historically contextual lens that seeks to understand not only the social cleavages between emigrants and indigenous societies, but also the multiple overlapping (and often contradictory) processes in which the two groups were intimately and mutually engaged, at both the macro (national) and micro (ethno-regional) levels; as well as the international tugs President Tubman confronted and shrewdly overcame.

Only then can we discern that the Tubman era was not primarily a period of emigrant suppression versus indigenous resistance, or True Whig Party hegemony versus multi-party democratic forces. But that it was in fact a period of intense collaboration, co-existence, co-optation, diffusion, and deep entanglement (to borrow a concept from the Cameroonian intellectual, Achille Mbembe) between the various political, cultural, and social elements, each extracting from the other its essential ingredients and vitality, in the production of a new reality.

In Liberia, the process of this entanglement was not new. For it had already acquired some intensity in the aftermath of the Barclay Plan of 1904. I like to think of the Barclay Plan as an unprecedented act of consensus-making, due to the unprecedented level of concessions President Barclay (1904-1912) forged with indigenous leaders in order to establish administrative control over interior hinterlands. Following the Barclay Consensus, indigenous politics and societies became officially incorporated into Liberia’s Western republican state – imbibing and effectively amalgamating their political, legal, social, and other systems into the state at different levels of differentiation and administration. It was under President Tubman, however, that the process of entanglement acquired new velocity and directions.

This is the kind of perspective which helps us explain, for example, why some half-century following Tubman’s death, ‘the imperial presidency,’ the ‘cult of the presidency,’ enclave economies, and the elaborate district and county structures – all consolidated during his rule – have neither been disavowed or decommissioned. But instead, they continue to persist, growing in strength. In other words, the Tubman era, despite the intense political antagonisms within the sphere of governmentality (what the Nigerian scholar Peter Ekeh terms the ‘civic public’), it was an era of great social complicity, collaboration, and accommodation between the various social groupings, such that a key element of the Tubman-era legacy is the very persistence and perpetuity which these phenomena, even as Liberia is now ruled by its indigenous majority elements. Therefore, it is not especially helpful to continue to discuss this period within the traditional lenses of ‘Americo-Liberian hegemony v. indigenous resistance,’ or ‘absolute domination v. suppression.’ The Tubman era was, I argue, a new phase of Liberia’s state development – a colonial transition of sort – in which new forms of political and social relations and collaborations took shape, for the purposes, I argue, of building a new nation and state.

That said, the question remains: how did President Tubman – a seemingly accomplished and consequential leader – suddenly fall from grace in Liberia’s academic, political, and folk consciousness? What are the premises of the dominant portrait about the Tubman era, and the basis for continued reticence about new attempts to carefully re-evaluate President Tubman’s legacy? How are we to properly understand the Tubman era and his legacy?

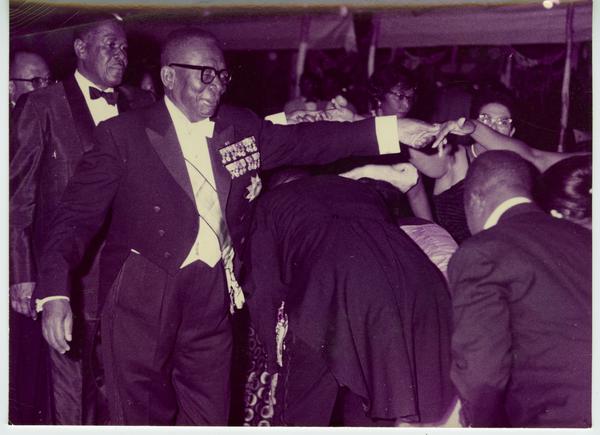

President William V. S. Tubman sits with Cabinet members in a boat in Venice, Italy. Photo courtesy of Indiana University

Two Schools of Thoughts

There are two major schools of thought which have influenced our thinking about the Tubman era and President Tubman’s legacy. In what follows, I sketch these two schools of thought and elaborate upon what I believe are credible contributions of the Tubman administration, despite views to the contrary – arguing that there is no one correct way of understanding President Tubman or his administration. I also reflect upon the critical ‘master narrative’ of Tubman’s legacy, and its enduring stranglehold on popular perceptions of the period. The effects of the broadly critical perspective of the Tubman administration, according to one keen observer, “has been to mobilize society into a negative attitude towards the Tubman era specifically, and Liberia’s past, generally,” thus, rendering the tasks of historical clarification, memorialization, and a careful re-examination of Liberia’s historiography ever more daunting.

The Pro-Tubman Narrative

The first school of thought is the largely sympathetic, pro-Tubman narrative which paints an almost saintly image of the man as this ‘great architect’ of nation-building, whose vision, foresight, and political acumen singlehandedly transformed Liberia into its modern version. This school of thought was for a time (throughout the 50s, 60s, and 70s) more dominant; but has since fallen into recession. Buried beneath the surface is an element of obsequiousness, especially by the government and government-affiliated writers who held obvious incentives to exaggerate the positive attributes of Tubman while downplaying the potential negative effects of his economic and political strategies on Liberia. For example, A. Romeo Horton, a former Liberian banker, statesman, and the intellectual father of the African Development Bank, describes the Tubman era as Liberia’s “Camelot Years,” in an apparent reference to the glory often associated with the reign of England’s mythical king, Arthur. The historians A. Doris Banks-Henries, Abayomi Cassell, and Lawrence Marineilli also write in this same pro-Tubman tradition.

Also reflected in this tradition is a certain solidarity by Tubman’s fellow African leaders, including Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia, Felix Houphouet-Boigny of Cote d’Ivoire, President Tafawa Balewa and Prime Minister Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria, and Julius Nyerere of Tanzania. Leopold Sedar Senghor of Senegal once described Tubman as the “founder of the Liberian nation, and creator of its modern economy, [who] has done more alone than all his predecessors did together.” Perhaps unable to anticipate today’s near-total erasure of Tubman’s saintly legacy, Senghor declared rather prematurely that “In his [Tubman’s] lifetime, he has entered into the history of the continent; never will he leave it.”

The Anti-Tubman, Anti-Imperialist & Anti-Colonial ‘Master Narrative’

The second, more dominant school of thought – what the historian Monday Akpan has termed the “master narrative” – paints the Tubman administration as a central part of the Americo-Liberian colonial and sub-imperial project. This school of thought argues that Tubman exploited and subjugated indigenous Liberians. In a sense, this master narrative can be viewed as an anti-imperialist, anti-colonial and a Pan-Africanist narrative.

Championed first by American and European scholars such as Raymond Buell, J. Gus Liebenow, George Dalton, and Robert Clower; and later by Liberia’s so-called “progressive” intellectuals and activists of the 1960s and 70s, this narrative was plugged keenly into the circuits of anti-imperialist and anti-colonial discourses and movements across Africa and beyond.

For “progressive” intellectuals like Amos Sawyer and Dew Mayson, H. Boima Fahnbulleh, Tokpa Nah-Tipoteh, Bacchus Matthews, George Kieh, and more recently Samuel P. Jackson, this anti-Tubman and anti-Americo-Liberian school of thought was a key part of Pan-African socialist and Marxist-Leninist movements against capitalist exploitation, wherein the thoughts of Karl Marx, Kwame Nkrumah, and George Padmore featured permanently.

Broadly speaking, it paints President Tubman as a grand-standing, cigar-smoking, pleasure-hugging, yacht-riding authoritarian dictator (a ‘benevolent dictator’) and American puppet – perhaps the most underachieving of all Liberia’s presidents. One young Facebook critic has gone so far as to compared Tubman to Germany’s Adolf Hitler, accusing him of presiding over Nazi-style concentration camps in Liberia.

No doubt, President Tubman’s authoritarian streak reflected itself in his dealings with opposition politicians. And there has been no limit to the extent of the fantastical charges that have been brought against him in this respect. But like its pro-Tubman counterpart, this anti-Tubman school of thought has tended to overemphasize Tubman’s political excesses, making little or no room for his important, positive achievements and contributions to Liberia’s state and nation building. For it is possible to credit great men and women without shutting our eyes to their faults.

There are also abundant criticisms of Tubman’s rule at the continental level, and within the global Pan-Africanist community. They are reflected from time to time in news articles like the one by Osei Boateng in the NewAfrican Magazine. In this essay, Boateng charges Tubman and leaders of the Monrovia Group (within the context of 1960s African unity) of representing “a western fifth columnist project” intent upon preventing the birth of a strong African continental union. Without delving into this continental debate, it suffices to say that despite Tubman’s strong alliance with the United States and the West, more broadly, his fears of Nkrumah’s socialist continental government were both genuine and legitimate; and a real threat to Liberia’s century-old democratic, free enterprise capitalist. Nkrumah’s own militant approach to Pan-Africanism dissuaded fellow African leaders from his cause. Not to mention the continued challenges posed by the tug and pull of former colonial powers, intent upon maintaining a stranglehold on their former colonies. The dawn of the Atomic Age and the East/West rivalry would also cast a long shadow over developments in places such as the D.R. Congo (formerly Zaire), Ghana, and elsewhere on the continent.

I argue that neither of the two schools of thought fully captures the essence of President Tubman’s legacy, or the full extent of his personal impact on Liberian politics, the nation, and the state. In the next episode, will I offer a different perspective on Tubman’s legacy, which sits at the middle ground between the two main schools of thought. For there is no one correct way of reading President Tubman or his administration.

Featured photo courtesy of Indiana University