Liberians have been put on edge since the announcement by the country’s health authorities of confirmed cases of COVID-19 on March 16. Despite the country’s successful 2014-2016 fight against the Ebola Virus Disease, the population remains anxious about the potential effects of this new pandemic on their livelihoods and their economic and health security.

Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone suffered the most decimating economic and human costs of the Ebola outbreak. These costs affected the social welfare gains made especially by Liberia following its deadly civil war, and the country’s progress towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals, now the Sustainable Development Goals.

The World Bank and Liberia’s Ministry of Finance and Development Planning estimated that Liberia saw a nosedive in its GDP from about eight percent to about half of a percent and an increase in its rate of poverty from around 5 percent to about 18 percent during the scourge of Ebola from 2014 to 2015. In terms of the human toll, Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone suffered a combined loss of more than 11,000 people by March 2016, when the World Health Organization declared an end to its public health emergency of international concern for the disease.

Drawing largely on this nasty experience with Ebola, Liberians now should use the Ebola experience to take immediate actions to support measures of their country’s health authorities to prevent and mitigate the spread and the impact of COVID-19 on their country.

Apart from its human toll, the COVID-19 pandemic is already severely ravaging the global economy. The managing director of the International Monetary Fund, Kristalina Georgieva, in a statement in late March, announced that the global economy was already in a recession due to the spiraling economic effects of the outbreak. She notes that the recession will be “at least as bad as during the global financial crisis of 2009 or worse.â€

Meanwhile, cases of Coronavirus infections are spreading, while the loss of human lives to the disease continues to rise staggeringly, though largely in Europe and the United States. The start of April 2020, for instance, witnessed “a near exponential growth in the number of new cases, reaching almost every country across the globe, with the number of deaths more than doubling in the week prior,†according to the WHO director-general.

Compared to the U.S. and Europe, the number of cases being reported in Africa remains low. These figures could rise quickly, however, amid concerns that the low numbers being reported are due to the continent’s limited testing capacity.

Already, major international airlines have suspended their flights due to weakening demand for travel, while countries have imposed travel restrictions across their borders, causing a drastic reduction in the flow of people and goods across the globe.

Factories in China, the source of the outbreak, remain closed, with severe disruptive effects on the global supply chain of goods. Leading automobile producers across Europe and the United States are experiencing a shortage of certain parts sourced from China that are needed for their production. The drop in China’s production has sent shocks across the global economy.

These shocks could be severe for African countries, including Liberia, that are primarily suppliers of raw materials to the global production chain, or for whom China is the major destination for their exports. Data from the Central Bank of Liberia places China as one of the top three destinations for Liberia’s exports, and a major buyer of iron ore, a major foreign exchange earner for Liberia. According to the Central Bank of Liberia’s Annual Report for 2019, iron ore alone accounted for about 42 percent of Liberia’s export earnings in 2019.

The Liberian economy, which has struggled to recover from the effects of the Ebola outbreak of 2014, had been projected by the African Development Bank to recover to the rate of 1.6 percent this year; this projection was based partly on the expectation of improvement in global iron ore prices. With no alternatives, this shock from the Chinese economy by COVID-19 could stall the recovery of the Liberian economy, as the prices of the country’s export commodities fall precipitously– a demand-side shock.

Apart from the demand-side shock, the effects of COVID-19 could also pose a supply-side shock to the Liberian economy. Many businesses (large, medium, and small enterprises) in Liberia rely on China for the goods that they sell. China is also one of the major suppliers of Liberia’s staple food rice, household materials, electronics, fabrics, vehicles, machinery, and spare parts.

Along with India, China accounted for more than half of Liberia’s total imports, including rice and food-related items in the last quarter of 2019, the Central Bank of Liberia reports. Reuters news agency reported on April 3, 2020 that India, one of the major sources of Liberia’s rice import, has suspended the export of rice. This suspension is due to the disruption by COVID-19 to the supply of migrant workers needed for rice cultivation in India and other parts of South Asia. This halt in exports by India has led to a surge in the demand for rice from Thailand, causing a rise in the global price of rice to what has been described by Reuters as “the highest in seven years.†This development could cause the price of rice and other related items to rise further in Liberia.

The inability of businesses to secure imports from their suppliers in China could slow down business activities across the country. With the prices of imported food items, especially rice, a major driver of inflation in Liberia, this disruption could affect the country’s already precarious food security position, with repercussions for the general health and economic security of the population.

Also, to see a severe effect from this slowdown is the segments of the population that eke their livelihoods from vulnerable employment or informal business activities, such as itinerary hawking. Returns from these activities are adequate only to provide this segment of the population a daily subsistence living, with no guarantee for social protection in the event of an economic downtown, such that which is being unleashed by the Coronavirus pandemic.

The Liberia Statistics and Geo-Information Services estimates that more than half of all employed persons working in Liberia rely on these activities to earn a living; they must work no matter what the prevailing situation in order to survive. With the slowing down of business activities, and the order to shelter in as part of measures to safeguard the public against the disease, their livelihoods will be severely affected by this economic downtown. Thus, absent an intervention, this disruption could plunge more than half of the country’s population, who are already impoverished, deeper into poverty and weaken their economic security.

The shocks of COVID-19 also have implications for the performance of the national budget and the strength of the Liberian dollar against other currencies, especially the U.S. dollar. As reported by the Central Bank, Liberia’s merchandise trade deficit stood around a whopping US$400 million (about 13 percent of GDP) in 2019; this gap was driven largely by the demand for rice, machinery, and transportation equipment.

Rice and other food-related items, together with office and household materials, vehicles, machinery, and spare parts accounted for more than half of payments on total 2014 imports, according to the Central Bank of Liberia. The potential loss in revenue or foreign exchange earnings from the drop in the global demand for iron ore due to COVID-19 could increase the pressure on an already weak Liberian dollar.

As Brahima Sangafowa Coulibaly of the Brookings Institution’s Africa Growth Initiative has noted, “these exchange rate depreciations will push up local inflation and trigger monetary policy and financial tightening.†The exchange rate for the U.S. dollar stands at L$196.96, a decrease of about 22 percent compared to 2019. All of these could negatively affect the government’s ability to honor its obligations in the national budget, its Pro-Poor Agenda, and further weaken an already fragile growth recovery.

Besides, the government’s ability to service its rising debt obligations, especially external debts, will be even more difficult with its revenue and foreign exchange positions declining. Data from the Central Bank of Liberia puts the external debt stock at more than US$800 million toward the end of 2019, about 26 percent of GDP. Outside any external debt intervention, this inability of the government to service its needs could create a long-run problem in which the government will have to focus on repaying its external debts in order to stay creditworthy at the expense of addressing the pressing the socioeconomic needs of the population.

The foregoing suggests that while the government’s current interventions are welcoming, more aggressive actions are required. The effects of COVID-19 demand forward-thinking actions that will improve the resilience of the health care system, businesses and the population, especially the poor and vulnerable, to the effects of the disease. Swiftly treating identified cases, containing the spread of the virus, and cushioning the economy from the effects of the disease are principal ways through which governments such as Liberia’s can minimize the effects of the pandemic.

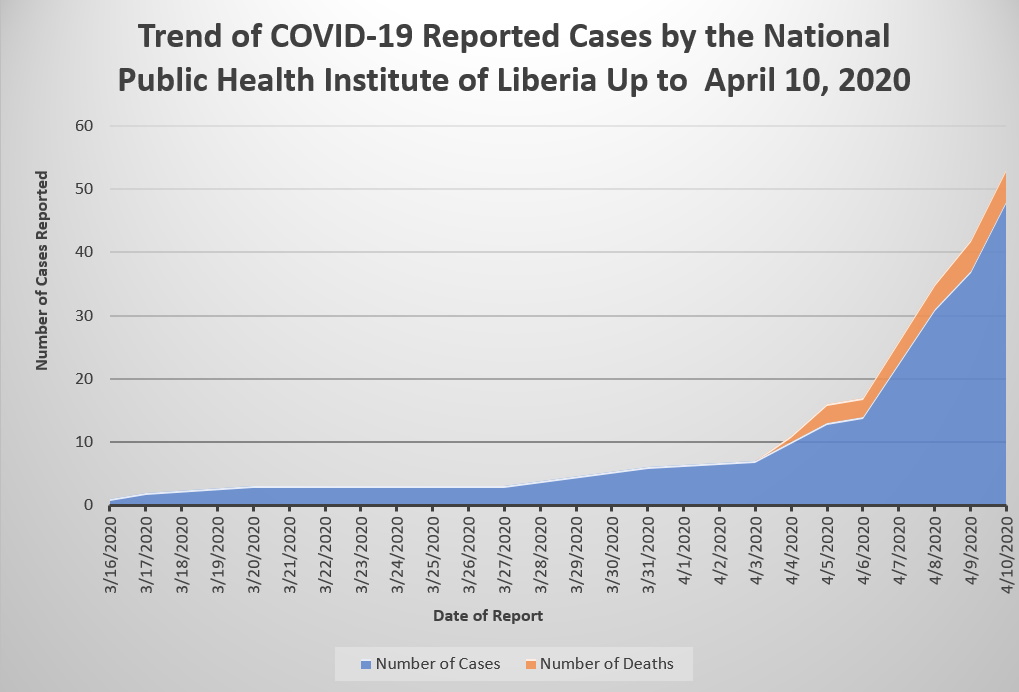

As of April 7, the Africa Centre for Disease Control and Prevention reported a total of 10,086 COVID-19 cases and 487 deaths in 52 African countries, including Liberia. This represented a 91 percent increase in the number of COVID-19 cases across the continent since March 2020. As of April 8, 2020, Liberia, on the other hand, reported a total of 31 cases and 4 deaths. This total number of cases reported in Liberia on April 8 represents about less than one percent of the 10,086 cases reported across the continent. Since March 16, when Liberia reported its first case, the number of new COVID-19 cases in the country, as seen in the featured image, has increased by about 3,000 percent, with the number of cases more than doubling between April 6 and 8. This alarming rate of increase in the number of cases, if not slowed or stopped, poses a severe danger to the country’s already severely challenged healthcare systems.

Suggested Policy Actions

A robust and well-sequenced multisector response led by the health sector is the first step in stopping the spread of the disease. In the absence of a robust health system response, actions taken to stop the spread of the disease would erratic and, at best, not in sync with scientific best practices.

A robust health response to COVID-19 requires a two-pronged approach:

- A public health response to the outbreak which is and should be led by the National Public Health Institute of Liberia, a government agency established immediately after the ebola crisis to prevent, detect and response to public health threats through the 15 county health teams.

- The provision of continuous routine health care services to the population. Hopefully, NPHIL has started taking the appropriate measures in support of these measures. Outbreaks can stretch already stretched health care systems. Like we saw during the Ebola crisis, women could not find places to deliver their babies, and malaria control, Tuberculosis, HIV, and immunization services were placed on hold.

Community cooperation is at a record high, compared to the Ebola outbreak when the public doubted the existence of the disease in Liberia. This doubt was due to the public distrust of the Liberian government, as many accused the government of using the Ebola outbreak as a gimmick to exploit the international goodwill to Liberia.

The current level of public support to the effort to contain the disease is, therefore, welcoming news. It is important that the government exploits this support and invests more in public awareness about the disease and the testing capacity of the National Public Health Institute. Increasing public awareness requires that all messages about the disease are clear, concise, and consistent. Such messaging minimizes fears of alienation while eliciting public support to the identification, tracing, and isolation of suspected cases of the disease for appropriate medical attention.

Testing provides reliable data for the appropriate level of treatment. No appropriate response can be developed for this outbreak without testing. Besides, testing also minimizes the dangers that frontline health workers face in caring for patients whose status of COVID-19 infection is unknown. Adequate testing also makes the disease surveillance system robust in detecting the virus, while minimizing the unnecessary use of health facilities as isolation centers for individuals suspected of having the virus.

Health facilities are not designed to isolate high containment pathogens; they also have inadequate infection prevention and control capacities. With adequate testing protocols in place, field epidemiologists or disease intelligence officers can do active surveillance activities. It is the development and the use of adequate testing protocols that has strengthened the health surveillance system in many African countries, including Ethiopia, Nigeria, Ghana, and Sierra Leone.

Once the response team is focused on providing adequate testing, beds for isolation, active community engagement, training of health care workers and providing needed personal protective equipment, managing COVID-19 in Liberia should be successful.

NPHIL’s capacity to respond has been tested with Ebola, Lassa Fever, Monkeypox, Scabies, and other diseases; containment and mitigation of the impact, following the same pattern, can be possible with COVID-19.

Contact tracing and active case finding are an integral and critical part of an outbreak mitigation strategy. Contract tracing is a core public health function that public health agencies have done for years. Diagnostic tests can confirm whether a person is infected with an illness. Contact tracing involves finding out who the infected person had contacts with so that those individuals can be alerted that they are at a risk of developing the illness and at risk of potentially infecting others in the community.

During contact tracing, health workers go door-to-door, village-by-village, or call using cellphones, asking contacts of the infected person if they’re feeling sick. They’re advised to self-quarantine for a period of time before an ambulance comes to pick them up to transport them to isolation facilities.

During the quarantine period, the health of the contacts can be monitored and health care or other services could be provided to them if they do develop symptoms. Also, it is important to make sure that people who have been exposed to the illness are not circulating in the community and further spreading the disease.

For the latter, the Ebola outbreak taught us critical lessons. The epidemic had severe and devastating impacts on the health system of Liberia, including the health workforce and supply chain. It stalled progress across the health sector, including progress towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals. It caused a deceleration of progress in reducing mortality due in part to the deaths resulting from Ebola directly. A similar deceleration in the mortality rate due to malaria could be attributed to the disruption to malaria treatment interventions.

Similarly, in 2014, DTP3 vaccine coverage dropped in Liberia from 76 percent in 2013 to 50 percent in 2014. A 50 percent reduction in access to healthcare services during the Ebola outbreak was estimated and this exacerbated malaria, HIV/AIDS, and tuberculosis mortality rates. Hospitals, health centers, and clinics were closed.

Other services affected included limited access to Caesarian sections and clinic attendance of under-five children, with a likelihood of a resultant high morbidity and mortality. Continuation of the implementation of the investment plan for resilient health services cannot be overemphasized during an outbreak response. Therefore, the Health Ministry should continue providing routine services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the economic front, this situation demands policy actions that will minimize the effects of these shocks from COVID-19 on businesses and the population, especially the poor and the vulnerable. It is important that these actions are not based on a master template, but tailored and specific to the socio-politically fragile state of Liberia. Such actions require that the government reorients its public financial management policies in the direction that increases or strengthens the safety nets for the poor and the vulnerable and reduce their exposure to deeper poverty and economic insecurity.

Enforcing the current shelter-in measures should consider the case of this segment of the population. Failure to account for the situation of this group could alienate them and undermine the legitimacy of the fight against the disease, a situation that was experienced during the Ebola epidemic in 2014.

Former finance minister Augustine Kpehe Ngafuan might have been speaking to this when he recently stressed the importance of increased attention by government financial managers to the allocative and the operational efficiencies in the management of Liberia’s national budget. Attaining these efficiencies requires that public resources be allocated to sectors and programs that generate the highest positive socioeconomic returns on the population in the fight against the diseases, with minimum leakages through fraud, waste, and abuse.

This also requires providing incentives to businesses to ensure the steady supply of basic commodities, such as rice and petroleum products, during this crisis without a significant rise in prices for these goods or their alternatives that may be sourced from elsewhere. Consideration should also be given to expanding the access of medium, small, and microenterprises to resources that would be needed to minimize or help them respond to the economic shocks of COVID-19 to their business productivity and growth.

These suggestions are not magic bullets in Liberia’s fight against COVID-19. They call attention, however, to some of the critical areas of governance that need reorientation as the country pursues actions to support the global efforts to defeat the Coronavirus.