“The duiker will not paint ‘duiker’ on his beautiful back to proclaim his duikeritude,” Wole Soyinka wrote, “you’ll know him by his elegant leap.”

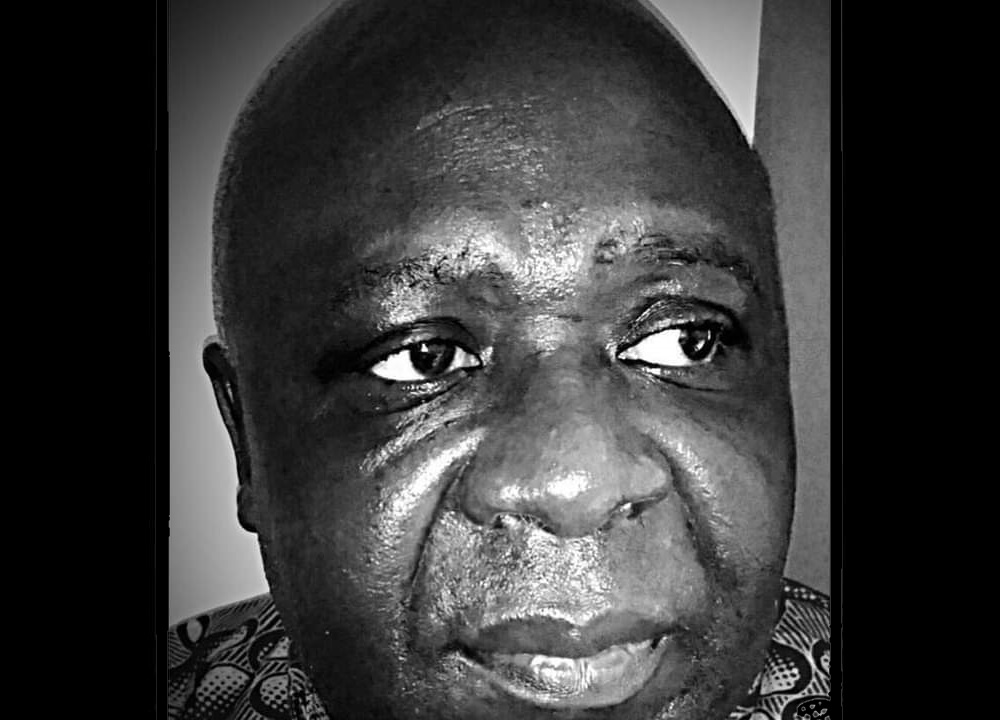

Not many people can reach through when your soul is battered, make you feel seen, communicate genuine care, and move you to laughter in those low moments. Thomas Jaye possessed this generosity of spirit. There was gentleness at his core. In an ancient, pre-colonial time, one can imagine him being a great healer, teacher, or wise, benevolent ruler. He was at once dignified, witty, and humble – a calming physical presence in that special way the truly great sons of Africa are.

TJ cherished friendships. He was a collector of friends, forever in search of renewed spirits. He never betrayed a confidence. Never kept speech. Never abandoned a friend. Never in my hearing uttered a negative remark or belittling word about anyone.

A great cook, consummate host, his home was a welcoming place for anyone to lay their head and rest. Principled and diplomatic, connected to progressive currents all over the continent, he was always planning, strategizing, learning, unlearning, with that wonderful, warm, authentic, infectious, spontaneous laugh.

One typical New Year email from him:

“Just to say that there is hope on the continent and the Pan-Africanist forces are marching on. There are difficult challenges but there is also hope. We hope to see you this year at home. Come take a look around. Your talents are needed.”

Tracing his years from a terribly hard young life to a prestigious position at the University of Liberia, we are moved by official portraits that valorize his career achievements. He would love it – without egotistical bluff or self-importance. We understood his ambition. We saw him traverse boundaries – geographic, academic, political, ideological, ethnic, and social. But memory is something else. Memory looks back to re-narrate a life with deep reflection. Remembering Thomas Jaye in his fullness is vital and elemental.

Young Jaye, the athlete. Footballer. Jaye, the militant grassroots activist leader. Movement for Justice in Africa stalwart TJ. Jaye, the Marxist-trained, socialist-leaning professor. Jaye, intellectual Pan-Africanist.

TJ, the boy, survived semi-slavery in the Krahn household he lived in away from home to attend St. Philomena Elementary School in Zwedru. Late for roll call Monday through Friday to finish all the morning work demanded of him in exchange. A cruel experience, this scarring initiation, submitting oneself to exploitation and abuse, clawing and scraping in order to grasp freedoms we were taught to believe western colonial education promised. He endured to move on to Bishop Ferguson High School in Harper but soon left to finish high school in Monrovia.

Hunger, humiliation, and deprivation in West Point, sleeping rough, lashed by rain, scorched by the sun, walking to Samford Dennis High School and later the University of Liberia.

TJ, the young man, stoned in Addis Ababa by reactionaries inflamed by foreign agents, hidden day and night in safe houses while there en route to pursue his dream of reaching the pinnacle of academia through the All-Africa Students Union co-founded by W. E. B. Du Bois.

Undergraduate studies completed in the Soviet Union at Moscow University, navigating a new foreign language and overt anti-blackness from fellow students, males especially. African students from everywhere looked to him to be the mediator, the negotiator, their counselor, advocate, and problem-solver. There were violent deaths, covered up with the bought silence of African ambassadors for scholarships and aid to keep flowing.

Graduate school student in London, the racist belly of white supremacist, capitalist, imperialist empire where he met his soulmate, Latifa Gawi, the lovely Black Tunisian woman he married. Liberian students called him Pa Jaye in cultural respect, for he always stood beside them through hard times. He started the Ph.D. mingling with Pan-Africanist freedom thinkers like Tajudeen Abdul-Raheem, whose unexpected death in 2009 crushed him to tears.

In between, before and after, too much else.

His urgency to return to a country haunted by spirits of the slaughtered, a region watered with revolutionary blood, a continent hemorrhaging between the talons of neocolonialism in the era of neoliberal capitalism. Taplah Wiah, Boley N’dorbor, Weewee Debar, his university comrades among so many others cut down. Amílcar Cabral, whom he greatly admired and often quoted, one among many extinguished bright lights.

He returned home an expert and authority in his chosen field and beyond, only to be demonized and ostracized inside his own country for belonging to a nonviolent organization formulated on the principles of social and economic justice to advance participatory democracy and social transformation through public education and political action. What sinister psychological methods were used, by those covert actors up there on Mamba Point, to convince gullible people that MOJA had the power to orchestrate the coup and ignite war?

TJ was Grebo aristocracy, though he never talked to me about that part of his life. No boasts or airs about lineage, bloodlines, and pedigree. Someone told me, I asked him, he umm’d in response. We who spoke with him often know he’d sometimes articulate through wordless sounds that left his answer to a question open to one’s own interpretation.

I probed, intrigued, an idealized, dream-like African past drawn from vivid myths and epics filling my mind. He laughed, saying it wasn’t that important. That was that. He could be unflinching about guarding his private life. But I couldn’t stop thinking about it because he fascinated me. He was just that interesting in my eyes. His secrecy piqued my curiosity all the more and I told him so.

We had discussed our national psycho-sociological predicaments many times. We talked about the profoundly, deeply lacerating problem of historical revisionism in the context of Frantz Fanon’s theory of social neurosis and psychopathology. We analyzed how erasure functioned to accelerate the demise of our cultural heritage, our national moral character, and our sovereignty. We talked about the dislocation and disruption of our multiple cultures, multiple languages, and individual and collective narratives – not homogenous, not monolithic, but intersectional. Blanks in his personal legend were to me a part of all this. And so I dug deeper into his background over time.

TJ’s lineage on both sides stretched back to the Songhai Empire. His parents were descendants of those migrants who fled its violent disintegration in the 14th century to first settle in the mythic Gedeh Mountains and later separate in groups to spread out from Grand Bassa to Cavalla, carrying a shared culture and language with linguistic variations. In another two centuries, the encounter with colonial powers would begin, three hundred years before those returnees whose ancestors were enslaved at various points along the Euro-American slave trade routes established the Liberian state in the 19th century.

His mother, Dweh Werlay, one of his father’s many wives, was from Forpo, a Grebo enclave in Grand Kru. She eventually moved away from his father’s compound, leaving behind her two young sons, TJ and his brother Andrew. Motherless.

His father, Paramount Chief Jacob Pleh Jaye, close friend to President Tubman, was from Tienpo in the Grebo heartland of lower Grand Gedeh, now River Gee, an area renowned for its powerful herbalists, fearsome occultists, and Kwee spiritualists. TJ’s father was rumored to be among the latter. Perhaps TJ grew up running from such overarching shadows. This could be why the number of times he visited his birthplace after his journey out into the world can be counted on one hand.

The name bestowed on TJ at birth was Tubman Shad Jaye, to seal Paramount Chief Jaye’s loyalty pledge to the president in the aftermath of the alleged assassination attempt on Tubman called “The Plot That Failed.” Giving their children foreign names had long been practiced by the Grebo through close association with foreign traders, centuries before the returnees brought the Anglo-European names that dominate our written history. TJ understood these entangled colonialist complexities and contradictions. He dropped the first name Tubman and middle name Shad, renaming and distancing himself from that history. Perhaps a priest suggested the name Thomas to ease his way through school. Whatever the reason, I understand his personal choice to break free.

I could tell a kind of loneliness took hold of him after his wife died in 2016. He worried about his son Mubarak, his only child, sorrowing for his mother. He was working in Ghana then to be closer to home, commuting by air between Accra and their London home, with frequent trips to Liberia.

He’d call, recounting scenes of suffering he witnessed in Liberia that he said could easily be alleviated with sound, visionary policies. The signs of generational malnutrition in young and old affected him deeply. Food is rotting on the roadside upcountry, he said once, his voice weighted with pain and exasperation. He talked about how instead of wasteful spending that did not directly impact vulnerable lives, the government could invest in strategic logistical transport, buy produce to support farmers and sustain local economies, and distribute food free nationwide in schools to encourage attendance and build up the next generation. This was what he thought the concept of national investment should be. He believed in practical, humane, Liberian-centered solutions.

It wasn’t easy for him in Ghana. Xenophobia, one group of Africans pitted against another, wore him out. “Nyeswa Accra,” the new private email name he took then, was symbolic. It revealed his weary groan. But all the traumas, exhaustion, demonization, regrets, and disappointments he bore lay buried deep under that surface-quiet lake within his soul.

The Kenyan scholar Keguro Macharia writes, evoking pre-colonial African epistemology:

If nothing else, I hope many of us will realize that suffering harm does not build character.

It wounds.

It harms.

It traumatizes.

It scars . . .

It makes building and sustaining relation very difficult.

We can imagine beyond suffering.

A few perceived TJ’s gradual collapse, visible yet hidden, until he succumbed to physical, mental and emotional weariness in the face of a brutal, relentless colonial inheritance.

He would still be with us, vibrant and breathing, if we understood how to work through all these traumas. This world is now a much more fearful place without him.

Rest in power now my friend. Thank you for being a constant sheltering mountain for so many through thunderous storms. Without beating your own drum, you quietly helped those without carry on.

Thank you for thinking with me through the complex question of belonging. Thank you for the brotherly embrace.

May our tears water your smooth passage. May you find bliss on the other side, and good magic.

You are leaving us behind brokenhearted.

You are leaving everything behind but you must carry this:

You were loved.

Cross well, Big Brother.